So, you want to start writing movies? Beware: Writing a movie is a completely different experience than writing a novel. There are different rules, different shortcuts, and, of course, different routes to stardom. Where to start? In screenwriting, there’s a very simple mantra: format, format, format. Like all aspects of art and creativity, you have to learn the rules first before you start to manipulate them. Ready? Let’s go.

Screenplay margins

First, let’s set up your margins: top margin at 1 inch, left margin at 1.5 inches, and right margin at 1 inch. The bottom margin should be at 1 inch as well, though it varies as there are rules if dialogue breaks between pages.

Screenplay font and size

On to the font: Courier or Courier New, size 12.

Okay, great. Time to get the party started. Type your opening transition. This is an (arguably) optional first step. Left justified, in all caps, write the glorious opening phrase:

FADE IN:

You’re basically done already.

Screenplay line spacing

Double space, staying left justified at 1.5 inches, and we’ll hit our first required element: the Master Scene Heading (don’t let off caps lock just yet.)

INT. LOCATION ONE - DAY

Also known as the slugline or master slugline, this element consists of three parts. The first is either interior (INT) or exterior (EXT), indicating if the scene takes place inside or outside. Rarely can you write both (INT./EXT.), but it has been done. The second part where the scene takes place; be sure to keep this location consistent if your characters ever go back. The last piece of the slugline is the time. Usually it’s as simple as DAY or NIGHT, but more specific times can be written if they are relevant to your story.

Single space. We’re on an action/description line now, so you can go ahead and turn off caps lock. Remember to always write in present tense—the flashbacks will be in present tense, the flashforwards will be in present tense… even the weird, parallel universe created when your protagonist fell into a temporal rift will be in present tense.

Set up the scene, but don’t blabber on too long. Each paragraph should be no longer than five lines. Keep breaking them up, in logical areas where the camera would naturally cut, to keep the page nice and digestible. You don’t want to intimidate Head Hancho over at Hollywood Movie Production Conglomerate with a big page of text, do you?

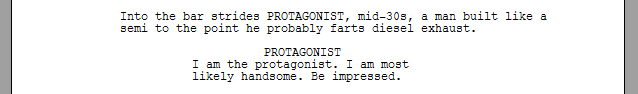

Okay, it’s about time to introduce your first character. For the sake of simplicity, let’s say you’re introducing your Protagonist.

Into the bar strides PROTAGONIST, mid-30s, a man so built like a semi he probably farts diesel exhaust.

Character introduction in a screenplay

When introducing a major character (and by “major” it’s generally meant “one with a speaking part”), put his or her name in all caps, but only the first time. Give them a little description as well, but don’t make the newbie mistake of trying to cast your main character. That’s not your job.

So the protagonist is in the bar now. As much as the silent thing is really working for him, it’s probably a good idea to have him speak.

Screenplay dialogue format

To write dialogue, start with an element called a character cue. That’s the part the actor will highlight when he’s trying to memorize his lines. Every character cue starts at 3.7 inches from the left of the page and is in all caps.

Soft return to a new margin of 2.5 inches. This is the dialogue, the section where the character’s words are written. It is always left justified at 2.5 inches, and shouldn’t go longer than 3 inches. It looks centered on the page, but don’t let that fool you, it’s still left-justified.

Now your protagonist is traipsing around the bar, talking. You’ve maybe introduced a side character as well, remembering, of course, to introduce him/her in all caps within your action line. Cool. But he’s rambling on now, making all the other bar patrons uncomfortable, so it’s time to get him out of there.

The way to do that is to create yet another scene, starting with a new master scene heading. Double space, hit caps lock again, and change up some scenery. Let’s bring in the Antagonist.

INT. EVIL LAIR – NIGHT

Perfect. Whenever you change time or location, you’ll need a new master scene heading, because it keeps everything clear and the readers oriented.

How to describe characters in a screenplay

Go ahead and introduce your antagonist. What is he doing? He’s working on some sort of Puppy Killing Device? Wow, what a tool. That’s the kind of evil genius who would probably create some sort of robot that serves him, huh?

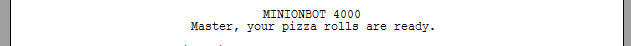

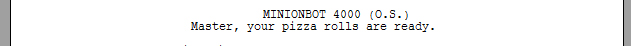

Speaking of his evil robot, it’s in the kitchen right off the main evil lair, cooking him some pizza rolls. He calls to his master:

However, the camera is still on the Antagonist. How can we indicate that MinionBot 4000 is in the scene, but off screen? We’ll put a dialogue note right next to the character cue. In this case, we’ll put “(O.S.)” there, which means “off screen.”

“Score!” squeals your Antagonist, dropping his screwdriver and prancing over to the kitchen. He’s changing locations, so that necessitates a new slugline, right? But really, he’s not going very far, and the time will be continuous over scenes… do we really have to do a whole new master scene heading?

Screenplay scene headings

No! Let’s do a secondary scene heading, also known as a sub-slugline. It’s still double spaced from the action line above, but we can chop of the “INT” part, since we know he’s still inside. And we know the time hasn’t changed, so go ahead and chop off that “ – NIGHT” part too.

So instead of writing

INT. EVIL LAIR, KITCHEN – NIGHT

just write

EVIL LAIR, KITCHEN

or even, simply

KITCHEN

While he’s waiting for his pizza rolls to cool, take a step back. Are you on page two yet? This is a good time to talk about page numbering. Why wait until page two, you ask? Because you never number page one.

Page number formatting and placement

One of the few things you’ll right justify is your page numbers. At .5 inch down from the top and 1 inch in from the right, put your page number and a period. That’s it. Nothing fancier needed.

Look, we left your antagonist for five seconds and he’s already about to chomp down on a still-scalding pizza roll. This is good for us, because the pain will trigger a flashback.

We’re changing time and location, so a new slugline is upon us; but this time, let’s add a little something extra, to help usher our readers back in time.

EXT. ANTAG’S CHILDHOOD HOME, BACKYARD – DAY (FLASHBACK)

Look at how much information is given in one line. It’s perfect.

Introduce your Young Antagonist like you would an entirely new character. It would be a new actor, so it makes sense, right?

Young Antagonist sits in his backyard playing with… can it be? Yes! A puppy! A twist of Shymalanian proportions! He and the puppy are having so much fun, it’s worthy of a montage. Let’s do it.

Start with a new master scene heading, but instead of the traditional three part structure, this will be formatted in two parts. First, you need to indicate a montage is happening, then what the main theme of the montage is.

MONTAGE – YOUNG ANTAG AND PUPPY ARE JOYOUS

Next, we’ll need to indicate all the quick shots in succession, as montages do. Each one gets its own action line, but be brief and indicate the shots by sticking a double hyphen before it.

MONTAGE – YOUNG ANTAG AND PUPPY ARE JOYOUS

— Young Antag and puppy on a beach, frolicking

— A park – Young Antag and puppy play fetch

— A romantic candlelit dinner

— The two on a roller coaster

Et cetera.

Now, to bring him back out of his montage, all we need is a new slugline:

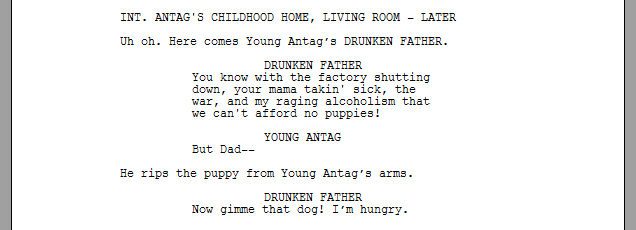

INT. ANTAG’S CHILDHOOD HOME, LIVING ROOM – LATER

Young Antagonist is arguing with his drunken father, the puppy clutched in his tiny, young arms. Chances are someone’s going to be interrupted—

Interrupted dialogue in a screenplay

Note when a character is interrupted, two hyphens indicate the cut off.

Yikes. Your bad guy’s backstory is really coming along nicely. But this is getting a bit depressing, so I think it’s about time we move back to the present.

INT. EVIL LAIR, KITCHEN – NIGHT (PRESENT)

You’re a pretty evil writer, giving your Antagonist a past like that. Look at him, he’s starting to cry! MinionBot 4000 is not programmed for this! He beeps, dings, and makes many sympathetic noises, but it does nothing for our Antagonist.

MinionBot 4000 watches Antagonist cry, emitting sympathetic BEEPS and CHIMES.

Whenever you list sound effects in text, they should be in all caps.

While your wailing Antagonist runs back into the main Evil Lair room to destroy his Puppy Killing Device in a fit of hysterical sadness, your Protagonist and his Sidekick show up, bloodied just enough to be impressive.

Well, I guess your Antagonist kind of solved the problem for them, so they’ll probably just stand there awkwardly while your Antagonist curls up into the fetal position on the floor. The Protagonist should say something, maybe something quirky like, “Well, that was easy.”

That’s a little caustic, though. Gotta keep your Protagonist sympathetic. So let’s have him say it in an awkward way, so we know that he’s willing to hit the one-liner but not at the expense of being a jerk.

Screenplay parentheticals

This is where will throw in a small element that goes by many names: some call them Actor Instructions, others Parentheticals, and even others call them wrylies. They go on their own line after the character cue, but before the dialogue, to indicate how the actor should intonate the subsequent dialogue. Left justified at 3.1 inches.

Do not overuse parentheticals; only put them in if you’re absolutely sure you need them. And even then, you should doubt yourself.

Well, that about finishes your story, right? Is it over 90 pages? Under 120? Great work!

Inserting voiceover in a screenplay

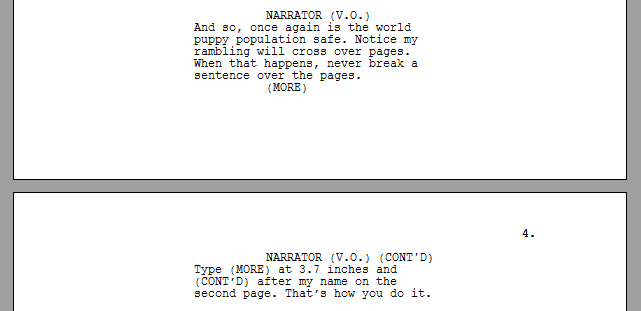

Let’s have the narrator sum it up for us in a Morgan Freeman style voiceover. However, he’ll prattle on a bit, so much so that his speech will start at the bottom of one page and continue onto the top of the next page.

So let’s start with the character cue, with the voiceover dialogue note “(V.O.)” afterwards. Type until you hit the 1 inch margin on the bottom. When you span pages with dialogue, and action lines too, you should never cut a sentence into pieces. Instead, leave white space at the end of the page and move the entire sentence onto the next.

When this happens with dialogue, type “(MORE)” at the bottom of the page (lined up with the character cue, which, as I’m sure you’ve already memorized, is at 3.7 inches) and then add “(CONT’D)” after the character cue (and dialogue note) on the next page.

How to end a screenplay

That’s enough from the narrator, let’s wrap this up by putting in our ending transition. Right justified, it can be either “FADE OUT.” or “FADE TO BLACK.”

Double space, then type out THE END in all caps. Give it an underline too. Beautiful, isn’t it? Keep in mind that screenwriting is a constantly changing industry, and many aspects of screenplay formatting can be done different ways. Use your discretion, research by reading scripts online, and always favor clarity and brevity above all.

So the next time you want to complain about Beverly Hills Tiny Dogs 3: Arf You, or that Michael Bay is making a movie about Lincoln Logs, don’t. Use it instead as inspiration. Certainly you can write a better movie than that, right? It’s time to prove it.