What do “Cinderella,” “The Ugly Duckling,” and David Copperfield have in common? They’re all “Rags to Riches” stories, building on a familiar storytelling pattern. What about Harry Potter, The Lord of the Rings, and The Matrix? Those all follow the “Monomyth” pattern, or the “hero’s journey.” Our most beloved works of literature stay with us for generations because they fit into the recognizable forms that we know and love.

Story archetypes put readers and writers on a familiar path, even though the scenery around them changes. The paths these stories take are direct reflections of what it is to be human and to try and make our way through the world, learning more about ourselves along the way. Let’s explore why these archetypes are such an important part of storytelling and how to use them in your own writing.

What are story archetypes?

Story archetypes are recognizable patterns in a story’s plot and structure that are repeatedly found in stories across time, cultures, and beliefs. These archetypes use a fictitious lens to convey a deeper truth. Using an archetype as the basis for a story creates a sense of familiarity and connection in the reader.

Many of these archetypes have been around as long as spoken language. People developed them as they gathered around the fire, telling stories to warn each other of danger, to teach important ideas, and to remind themselves that there was hope even when the world seemed dark. These stories stayed with us, always retaining the core lessons that were at their heart. By using story archetypes to inform your writing, you’re becoming a part of our collective storytelling history.

Why are story archetypes useful in writing?

Story archetypes give your plot a roadmap to follow, as well as an idea of the themes and conflicts that your characters are going to encounter along the way. This doesn’t mean that all stories within a certain archetype need to be the same—all of these archetypes can be transposed onto any genre, from middle-grade horror to sword-and-sorcery fantasy to the sort of highbrow, character-driven fiction that gets featured on Oprah. Every dramatic work will have core elements in common while remaining uniquely individual at the same time.

You can use these basic plots to give your ideas direction and to bring clarity to your story. By finding the archetype that resonates most with the message you’re trying to send, you’ll be able to shape the path your characters take in a way that readers will be ready to follow, to engage with, and to immerse in because it puts them in the familiar landscape of other stories they’ve loved. This allows you to take a step back and concentrate on the things that matter: building your world, crafting dynamic characters, and communicating powerful themes that make your readers see the world in a new way.

Story archetypes vs. character archetypes

In the craft of storytelling you’ll come across two major kinds of archetypes: story archetypes and character archetypes. Both of them show us familiar literary patterns that we recognize from stories, histories, and experiences.

Story archetypes are the blueprint for the world in which these characters live—the pattern of events, themes, and ideas that lead the plot and the character arcs from start to finish. By following these templates, we can create worlds that we know will resonate with our readers.

Character archetypes are patterns that characters fall in to, like the templates of the hero, the villain, the sidekick, the guardian, and the trickster—all common archetypes you’ll find throughout literature. They’re the classic personalities that populate every good story.

The ultimate list of story archetypes

Over the years, several scholars have tried to compartmentalize the vast web of dramatic work into manageable lists. These lists of basic plots have become an invaluable tool for writers, readers, and literary scholars to examine the connections between stories and how older tales inform their descendants, and how the ideas presented in those stories can still be relevant today.

You’ll see that many of these story types overlap, as these theorists tried to put similar ideas into their own words. You may find that one system of story archetypes resonates with you more than others, or you may feel best using a combination of more than one system. Don’t feel like any of these story archetype lists are a rigid rule book—instead, they’re tools for you to guide and enhance your writing.

1. The Hero’s Journey

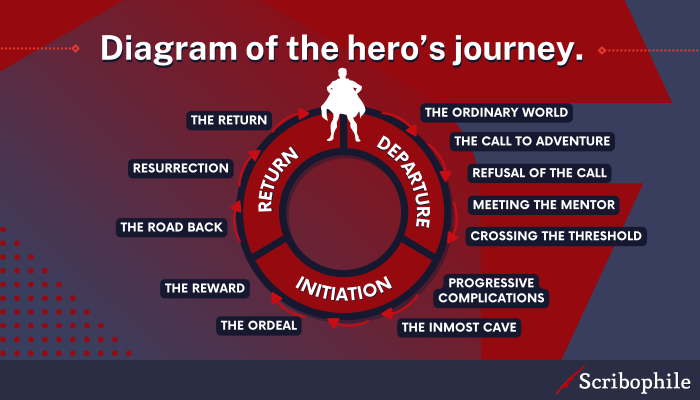

Also called the “monomyth,” the Hero’s Journey is one of our most common universal story archetypes. Just about every classic adventure story and myth follows this archetype, as well as all the contemporary stories that have been inspired by these classics. Originally created by the scholar Joseph Campbell and then later refined by screenwriter Christopher Vogler, the Hero’s Journey is a series of twelve stages the main character goes through as they’re drawn into their adventure, work towards their goal, and then come out the other side of it.

These are the twelve stages of the hero’s journey:

1. The Ordinary World

In which we meet the main character, or the hero, and get to see him or her in their familiar, mundane world. It sets the stage, shows the reader the hero’s relationship with the world around them, and hints at the conflicts to come. This also reminds the reader that most heroes come from humble beginnings, just like us.

2. The Call to Adventure

In which the hero is presented with a challenge or a problem that causes them to embark on their adventure. It might be a result of a malevolent force, a change of circumstance, or their own curiosity, but it will change the landscape of the life that they knew. In story structure, we would call this the inciting incident.

3. Refusal of the Call

In which the hero starts to have second thoughts about the wisdom of their venture. They may think that they’re not the right person for the task, or they might be afraid of what will befall them, or they might realize that what they actually want is just to make a cup of tea and watch Netflix instead. During this stage, the hero will take a hard look at what’s important and why they need to move forward.

4. Meeting the Mentor

In which the hero reaches the first turning point in their journey. They’ve mentally prepared to go on their quest, but they don’t yet have the tools they need to succeed—whether this is a physical object, information, a specialized skill set, or even a jolt of self confidence. At this point they’ll meet another character who is able to give the hero what they need to move on to the next step.

5. Crossing the Threshold

In which the hero crosses the line between the world they knew and the world ahead, a point at which they can no longer turn back. This might be something like leaving their home, taking a job offer, or taking some sort of action that they can’t take back. Up until this point, the hero has been battered by things happening to them; now they’re beginning to make choices of their own. This moment usually marks the start of the second act.

6. Tests, Allies, Enemies

In which the hero is fully immersed in the world of their quest and needs to navigate a string of obstacles along the way. The hero will meet new friends and new enemies, sometimes being misled as to which is which. This stage of the hero’s journey tends to take up the bulk of the second act of the plot, and is when most of the supporting characters are introduced.

7. Approach to the Inmost Cave

In which the hero approaches the seat of their objective. This might be an actual place, such as the villain’s lair, or it might be the culmination of all the work the hero and their friends have done, or the breaking point of their own insecurities and fears. This stage is a bit like a reversal of the threshold; it puts the final line within sight, beyond which the world will be irrevocably changed yet again.

8. The Ordeal

In which crossing the threshold does not go even remotely as planned. This stage has been called the “black moment,” the “belly of the whale,” and the “dark night of the soul.” The hero confronts their greatest fear and survives—but not unscathed. They go through a metaphorical (or literal) death and rebirth, emerging from their ordeal transformed and ready to take on the next stage of their adventure. This is usually the zenith of the hero’s character arc.

9. Reward (Seizing the Sword)

In which things start looking up—for a little while. The hero reaches their goal of obtaining a sacred object, learning valuable information, or reaching a loved one. They’ve been through a lot, fighting tooth and nail to reach their destination, and now they finally have something good to show for it.

10. The Road Back

In which the hero attempts to return home with their spoils, but finds that their journey has created consequences that they have to deal with first. As a result of reaching their goal, new adversaries have been launched into action. Here there is an echo of the call to adventure; the hero can choose to abandon their journey now that they have what they’ve been fighting for, but instead they choose to put themselves on the line for the greater good.

11. Resurrection

In which the hero faces their greatest battle of all. They’re faced with a challenge that goes far beyond their own goals, something that affects the good of the wider world around them. In this moment the hero will show that they’ve learned from the mistakes of their ordeal and go through their final transformation into a true hero.

12. Return with the Elixir

In which the hero finally gets to go home to the normal world… but they’re no longer the same person they were when they left. The hero has grown, learned, and become the person they were meant to be all along. They also bring with them the goal they went searching for, whether it’s a holy object, knowledge, or a new sense of self. The hero has emerged triumphant, but some scars may never go away. Now they get to begin the next chapter of their life.

Star Wars, The Odyssey, and To Kill a Mockingbird are all examples of the Hero’s Journey, or monomyth, archetype.

2. Kurt Vonnegut’s 6 story archetypes

Kurt Vonnegut developed a system of basic plots based not on the actual events of the plot, but on the arc the main character takes as they make their way through them. There were a finite number of these story arcs, he argued, and every story since the creation myth of the Bible follows one of these arcs. (In fact, it was the parallel between the story of the garden of Eden and the story of Cinderella that gave Vonnegut this idea in the first place.)

Vonnegut’s system has since been confirmed by a study feeding almost 2,000 classic stories into a complex computer system that examined both the story arcs—or the plot—and the character arcs—or the emotional journey of their heroes. Here are the classic story archetypes they found.

1. Rise, or “Rags to Riches”

In which a poor protagonist begins in an adverse circumstance and begins an upward journey towards a better life. These stories are popular because readers enjoy seeing someone less privileged make their way to better circumstances through their own determination, resilience, and cleverness. A Little Princess and Matilda are examples of this story type.

2. Fall, or “Riches to Rags”

In which the hero begins in a position of privilege and, through their own mistakes or misdeeds, cause their own downfall. These stories often serve as cautionary tales about what happens when we allow our anger or avarice to devour us. The Catcher in the Rye and The Picture of Dorian Gray are examples of this arc.

3. Fall Then Rise, or “Man in a Hole”

In which the hero faces a catastrophe that sends them plummeting into trouble, and spends the story fighting their way out. These stories show readers that we have the strength to overcome the obstacles that life throws in our way. The Hobbit and The Hunger Games are examples of this story type.

4. Rise Then Fall, or “Icarus”

In which the hero improves their circumstances but, usually through their own pride, loses what they’ve gained and ends up worse than they were before. The shape of this arc is most similar to the story device known as Freytag’s Pyramid, and inspired Gustav Freytag in his work. The Great Gatsby is a classic example of this story arc.

5. Rise Then Fall Then Rise, or “Cinderella”

In which a poor protagonist acquires power—which might be external or internal—comes up against an insurmountable obstacle and ends up worse than before, and finally claws their way past their misfortune and limitations to a positive new beginning. These always have a successful or happy conclusion. Most contemporary romances follow this pattern. Jane Eyre and Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca also follow this story arc.

6. Fall Then Rise Then Fall, or “Oedipus”

In which the hero’s circumstances crumble because of some misfortune, and the hero manages to pull themselves back up—but lets their own major character flaw drag them back down to their unfortunate end. Much like the “Fall,” this story type warns us to be mindful of our weaknesses and allow our strengths to guide us instead. Frankenstein is a classic example of this story type.

While most stories will follow these arcs from start to finish, many will have “mini-arcs” throughout the plot as the hero comes up against new challenges and discovers new strengths along the way. Feel free to try mixing various story arcs as you explore your characters and their world.

3. Christopher Booker’s 7 story archetypes

Story scholar Christopher Booker came up with a list of seven archetypes, and his list is the one most commonly referenced by writers and academics today. These seven basic plots focus on the sort of journey the main character takes and the obstacles they overcome. He believes that all stories and character arcs fall under one of these story archetypes, or a combination of several of them.

Here are Booker’s 7 universal story types:

1. Rags to Riches

In rags to riches story structure, the main character begins in a position of destitution or some other disadvantage, and comes across a change in fortune. This might be a shift in wealth and class, as we often tend to think of in these stories, though it can also come in the form of beauty, influence, or respect. These stories always have a happy or cheerful ending.

Sometimes these stories might go through a second arc in which the hero loses their new fortune and has to work to get it back. These are effective because while the first story arc is usually a result of luck, the following story arc happens because the character takes responsibility for their fate and grows as a person because of it.

Examples of the Rags to Riches story archetype are The Prince and the Pauper and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

2. The Quest

The protagonist sets off on a journey to reach a tangible objective. This might be something like a sacred place, an object of power, a person, or hidden knowledge. The hero might choose to go on this quest for their own reasons, or it might be thrust upon them by a mentor figure or loved one.

Once the hero begins their quest, they must fight obstacle after obstacle in order to reach their goal. They won’t come out of their challenges unscathed, but they will have grown and learned something about themselves along the way.

Examples of the Quest archetype are King Solomon’s Mines and The Raiders of the Lost Ark.

3. Rebirth

Rebirth stories are often found in religious and creation myths, but the “rebirth” can simply be a dramatic transformation of the main character. This transformation often begins with events beyond the protagonist’s control and culminates in their own choices and self-awareness as they work towards a better future.

These stories show how a deeply flawed person can, through powerful experiences and deep personal introspection, become someone who makes a positive impact on the world.

Examples of the Rebirth story archetype are A Christmas Carol and Silas Marner.

4. Overcoming the Monster

This story archetype is one we recognize from much of our mythology and folk stories, in which a human character much like any one of us fights an antagonist much bigger and scarier than they are. The antagonist might be an actual monster, a monstrous person such as an abuser or murderer, a faceless corporation engaging in unethical practices, an internal “monster” such as addiction or mental illness, or any other external antagonistic force.

Readers love these stories because they show us that even though monsters exist in our world in some form or another, they can be defeated with enough courage. Neil Gaiman summed this up perfectly when he said, “Fairy tales are more than true—not because they tell us dragons exist, but because they tell us dragons can be beaten.”

Examples of the Overcoming the Monster story structure are the biblical story of David and Goliath and Moby Dick.

5. Comedy

Comedies in literature are distinguished by a happy or cheerful ending. Shakespeare’s plays were broadly divided into Comedies and Tragedies—if nobody died, it was considered a comedy, and if everybody offed each other until there was no one left standing, it was a tragedy.

In literary terms, a comedy is a story rich in dramatic irony, where the readers or the audience always knows more about what’s going on than the characters do. We get to watch a humorous character make grand yet very human mistakes in life and love, knowing that they’ll somehow find their way to a happy ending.

Examples of the Comedy story archetype are A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Pride and Prejudice.

6. Tragedy

While comedies show us how our mistakes are what make us human and alive, tragedies show us how our innate weaknesses have the potential to destroy us if we let them. These stories follow a fundamentally good character with a major flaw—such as greed, pride, or anger—that leads to their downfall.

These stories work well as cautionary tales for our own flaws, because very often the weaknesses in these characters are things we can recognize inside ourselves. This is what makes them so compelling and powerful.

Examples of the Tragedy story archetype are Shakespeare’s Othello and the Greek play Oedipus Rex.

7. Voyage and Return

These stories follow a hero who goes on a journey to a new, exciting and strange land that’s completely different from anything they had known before. It might be a place full of barely-imagined beings, such as Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, or it might be something in our own world: a new country, an unfamiliar culture, or a completely different set in society.

Unlike the Quest, the hero won’t necessarily have a goal at the end of the road; these stories are about the journey, the people the hero meets, and the things they learn about themselves and their perception of the world along the way. These stories work very well as metaphors and allegories for contrasting cultures, prejudices, and stigmas in our own world.

Examples of the Voyage and Return story archetype are The Odyssey and Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere.

4. Ronald Tobias’s 20 story archetypes

The author Ronald B. Tobias took these preceding archetypes further and created a list of 20 basic plots and archetypes based on the central idea or theme of the story. Many writers have sworn by his classification system as a jumping-off point for their own stories. Here are the 20 he chose:

1. Quest

The hero goes looking for something or someone that affects a world much bigger than themselves. This can also be an internal quest, as they search for courage or inspiration within themselves.

2. Adventure

The hero goes on a journey, but unlike the Quest, Adventure focuses more on the hero’s experiences than the destination. This is much like Booker’s “Voyage and Return” archetype discussed earlier.

3. Pursuit

Like many spy thrillers, this story focuses on the hero pursuing a villain or being pursued by one, always doing whatever they can to stay one step ahead.

4. Rescue

Someone the hero loves or needs has been lost, captured, or waylaid and the hero goes after them. Many classic fairy tales follow this story, which creates a triangle between the rescuer, the rescued, and the villain.

5. Escape

This may follow the rescue, or your story may begin here. The hero escapes from a prison (real, metaphorical, or imagined) and does their best to fight their way home.

6. Revenge

The hero seeks retribution against a person or group that has wronged them, very often becoming just as bad as their enemies in the process.

7. Riddle

Like the traditional mystery or detective story, the hero must unravel a series of challenges to gain new understanding and reach a solution.

8. Rivalry

The hero has to compete against an opposing force, whether that’s in love, sports, business, or the arts. In these stories they need to balance their ultimate goal with their own personal values and morals.

9. Underdog

A rivalry with a significant shift in status. The hero is at a physical, financial, or cultural disadvantage and needs to exercise greater cunning and determination to beat their opponent.

10. Temptation

The hero faces an internal conflict with their own weaknesses, such as extreme pessimism, addiction, or insecurity. They navigate their world while fighting against these weaknesses—sometimes successfully, sometimes not.

11. Metamorphosis

A physical transformation, usually due to some supernatural force, in which the hero either finds a way to turn back into who they were or learns to build a new life as what they’ve become.

12. Transformation

An emotional or spiritual transformation (as opposed to the literal transformation of the metamorphosis); the hero deals with an extreme change in their circumstance and undergoes a positive shift because of it.

13. Maturation

The classic “coming of age” tale where the hero has to grow up in response to what’s happening around them, gaining a new understanding of the world and a new sense of purpose.

14. Love

A story in which two lovers find each other, become separated by external forces or by personal insecurities, and overcome their obstacles to be reunited.

15. Forbidden Love

A love story in which the two lovers meet in spite of the rules of their society, cultures, or personal circumstances. These stories may focus on their inner conflicts and divided loyalties.

16. Sacrifice

The central character makes a bold sacrifice for the good of their loved ones or the world around them, showcasing human nature at its greatest potential. This will usually come at the end of a difficult period of growth for the hero.

17. Discovery

A story of revelation in which the hero learns something that shakes their perception of the world they know, and has to adapt and understand what that revelation means for them.

18. Wretched Excess

The protagonist lives a life far beyond what is socially acceptable, making hedonistic choices that alienate what’s truly most important and ultimately lead to their downfall.

19. Ascension

The “rags to riches” story, whether by material wealth or by personal growth, in which the hero rises to become something greater than what they started out as.

20. Descent

The opposite story arc to “Ascension,” in which the central character begins in a place of contentment or privilege and watches their world crumble as a result of their own hubris or mistakes.

Although these archetypes don’t represent a full story by themselves, they can give you an idea of the general arc and theme you might want your story to take.

5. Georges Polti’s 36 story archetypes

In the late 19th century, scholar Georges Polti created his list of basic plots by examining common themes in Greek and French literature. He called these “the 36 dramatic situations.” Rather than reflecting a story arc or a central idea, Polti based his list on the sorts of conflicts that could be present in a story (conflict, of course, is what leads a story into “dramatic situations.”)

He believed that all major plot points in a story stemmed from these 36 universal conflicts:

1. Supplication

The central character or group of characters appeals to a higher power (usually a political power, but not always). A decision is made, and the decision launches the characters into action.

2. Deliverance

A conflict has been caused unintentionally by a person or group of people, and the hero enters to deal with this new threat.

3. Vengeance for a crime

The hero seeks revenge for a wrong that has been committed against them, or they find themselves the unwitting subject of another’s vengeance.

4. Vengeance taken for kindred upon kindred

Revenge taken by one family or organization on another, or by one family member against another family member.

5. Pursuit

The hero flees pursuit from an accident or misunderstood conflict; the hero must avoid their enemies as well as find a way to prove their innocence.

6. Disaster

A great defeat of a powerful ruler, society, or organization, and the aftermath of that defeat.

7. Falling prey to cruelty or misfortune

The classic tragedy in which bad luck or the hands of fate sends the hero spiraling into their journey.

8. Revolt

A revolution in which a cruel leader is plotted against by a group of conspirators, or a group of heroes seeks to change the way things are in their society.

9. Daring enterprise

The “Quest” in which the hero or group of heroes goes on a journey to gain something precious and overcome an adversary.

10. Abduction

Someone is taken captive and the hero has to go on a journey to save them, defeating the villain who kidnapped them and bringing the captive home safely.

11. Enigma

A mystery or riddle that the hero needs to solve before time runs out, gaining a better understanding of the world in doing so.

12. Obtaining

Two or more opposing parties are after the same object, which may be supernatural, financial, or of cultural importance.

13. Enmity of kinsmen

Hatred brewing within a family (or family unit, such as a workplace) and the choices made in response to that hatred, and their consequences.

14. Rivalry of kinsmen

Two or more family members fighting over a common goal, such as an inheritance or love for the same person.

15. Murderous adultery

Two lovers plot to kill the spouse of one or both partners for romantic or financial gain.

16. Madness

The villain has lost their mind and lashes out at the hero, and the hero must escape an adversary who is unable to reason; common in horror stories and thrillers.

17. Fatal imprudence

A hero or leader makes an arrogant mistake which costs them their objective, their loved ones, or their own life.

18. Involuntary crimes of love

Two lovers accidentally commit a crime because of their love, such as one lover killing a rival, and then having to deal with the consequences of those actions.

19. Slaying of a kinsman unrecognized

The hero accidentally kills a family member or loved one, not recognizing them because they’ve been disguised or the hero has had their senses compromised.

20. Self-sacrificing for an ideal

The hero sacrifices their life or well-being for a greater purpose, such as the safety of the wider world or an important message.

21. Self-sacrifice for kindred

The hero sacrifices their life, ambitions, or well-being for the sake of a loved one, often gaining a new understanding of their priorities and what’s most important in life.

22. All sacrificed for a passion

A fatal passion, which may be for love or another objective, which devours the hero’s life. This might be something like a king giving up their kingdom to marry a commoner, or an artist putting everything on the line for their art.

23. Necessity of sacrificing loved ones

A hero is forced to sacrifice someone close to them for the greater good or to prevent an even greater loss.

24. Rivalry of superior and inferior

The “underdog” story in which the hero is at a visible disadvantage and has to overcome a more powerful adversary.

25. Adultery

Two lovers conspire against the spouse of one or both partners, which often turns on them and puts the lovers in a worse position than when they began.

26. Crimes of love

Two lovers break a cultural or societal law by initiating a relationship, needing to choose between their love and their competing values.

27. Discovery of the dishonor of a loved one

One character learns that their friend or family member has committed some crime or acted shamefully, and the two characters need to deal with the consequences of the discovery.

28. Obstacles to love

Two lovers can’t be together until they overcome the challenges along the way.

29. An enemy loved

Two characters are in conflict over their feelings for a third, such as a sister dating a boy who bullies her brother. The love for the enemy will cause conflict between the two characters.

30. Ambition

The hero seeks an objective which is beyond their reach and has to overcome a range of challenges, internal and external, to reach it.

31. Conflict with a god

A mortal comes into conflict with a supernatural being or an adversary much greater than themselves.

32. Mistaken jealousy

A character is given false information or makes incorrect assumptions that leads them to be jealous of another for the wrong reasons.

33. Erroneous judgment

A character is wrongfully accused of a crime, which may have been engineered intentionally by the villain, or may be a product of unfortunate circumstances.

34. Remorse

The central character commits a crime or lives in a way that they’re not proud of and begins a slow path towards redemption.

35. Recovery of a lost one

The hero goes on a journey to retrieve a loved one; unlike the Abduction, the loved one will have been lost by their own mistakes or by a force of nature, rather than an antagonist.

36. Loss of loved ones

The hero sees a friend or family member killed or wrongfully taken from them, changing the world for the hero and setting them on a new path.

Similar to Tobias’s thematic story archetypes, Polti’s “dramatic situations” don’t reflect your entire story from start to finish—rather, they give you a place to begin and a place on which to hang your story’s major plot points, opening up paths you might not have otherwise discovered.

6. The Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index

The Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index is a fascinating classification system that specifically focuses on European folklore. Often called the “Dewey decimal system for fairy tales,” this system—compiled over several decades by the folklore scholars Antti Aarne, Stith Thompson, and Hans-Jörg Uther—is believed to cover more than 2,500 traditional folk tales, drawing parallels between stories with similar roots across cultures. Through it we can see how the same universal story ideas grew independently across the world.

Their index is divided into 7 broad categories. Each of those categories contains several slightly narrower subcategories, and all of those subcategories contain more specific subcategories of their own, and those contain their own individual story types, and so on. Forever.

While listing all 2,000+ would take several rather heavy volumes, here are the central categories that Aarne, Thompson, and Uther believed encompassed all the stories in the world.

1. Animal Tales

A few of the subtypes of stories in this category are:

-

Wild Animals (#1—99)

-

The Clever Fox (And Other Animals) (#1—69)

-

Wild Animals and Domestic Animals (#100—149)

-

Wild Animals and Humans (#150—199)

-

Domestic Animals (#200—219)

2. Tales of Magic

A few of the subtypes of stories in this category are:

-

Supernatural Adversaries (#300—399)

-

Supernatural or Enchanted Relative (#400—459)

-

Supernatural Tasks (#460—499)

-

Supernatural Helpers (#500—559)

-

Magic Objects (#560—649)

-

Supernatural Power or Knowledge (#650—699)

3. Religious Tales

A few of the subtypes of stories in this category are:

-

God Rewards and Punishes (#750—779)

-

The Truth Comes to Light (#780—799)

-

Heaven (#800—809)

-

The Devil (#810—826)

4. Realistic Tales

A few of the subtypes of stories in this category are:

-

The Man Marries the Princess (#850—869)

-

The Woman Marries the Prince (#870—879)

-

Proofs of Fidelity and Innocence (#880—899)

-

Good Precepts (#910—919)

-

Clever Acts and Words (#920—929)

-

Tales of Fate (#930—949)

-

Robbers and Murderers (#950—969)

5. Tales of the Stupid Ogre/Giant/Devil

A few of the subtypes of stories in this category are:

-

Labor Contract (#1000—1029)

-

Partnership between Man and Ogre (#1030—1059)

-

Contest between Man and Ogre (#1060—1114)

-

Ogre Frightened by Man (#1145—1154)

-

Man Outwits the Devil (#1155—1169)

-

Souls Saved from the Devil (#1170—1199)

6. Anecdotes and Jokes

A few of the subtypes of stories in this category are:

-

Stories about a Fool (#1200—1349)

-

Stories about Married Couples (#1350—1439)

-

Lucky Accidents (#1640—1674)

-

Jokes about Clergymen and Religious Figures (#1725—1849)

-

Anecdotes About Other Groups of People (#1850—1874)

-

Tall Tales (#1875—1999)

7. Formula Tales

A few of the subtypes of stories in this category are:

-

Cumulative Tales (#2000—2100)

-

Chains Based on Numbers/Objects/Animals/Names (#2000—2020)

-

Chains Involving Death (#2021—2024)

-

Chains Involving Eating (#2025—2028)

-

Catch Tales (#2200—2299)

As you can see, the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index is very much reflective of the time in which it was created and the values that people placed in their storytelling; were it to be written in the twenty-first century, it would likely look quite different. However, it gives us a marvelous insight into how traditional stories emerged from a handful of seeds—seeds which are still influencing the stories we tell today.

You can read more about the specific story archetypes in the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index here.

Within these distinctive story archetype systems we can see that the writers, academics, and researchers who painstakingly put them together were circling around the same core storytelling ideas. All of the stories present in literature and film stem from the same human desires, strengths, weaknesses, and relationship to the world around us, which is why we see the same central themes again and again. By tapping into these universal stories, you can create a world that will feel real and relevant to the reader.

4 tips for using story archetypes in your own writing

Using a predefined template for your story might sound limiting at first, but you’ll quickly see that it’s actually very liberating. Using story structure doesn’t mean that you’ll be writing something that has been done a thousand times before—it means that you’ll be writing down your own unique, groundbreaking ideas in a pattern that your readers will already know from the other stories they’ve read, and from their own experiences. This means that your story will feel honest and true to them right from the start.

Here are a few tips for using story archetypes in your own writing.

1. Use archetypes as a story framework

When you begin writing a story, try working with one of the major story archetypes in mind. Using a story archetype as a template for your own story is a great place to start because these templates have been proven to work for centuries in just about every genre. By choosing a story archetype that you know is already successful, you’re more likely to write a successful and satisfying story of your own.

However, this doesn’t mean that your story will be a copy of other stories that have used that archetype before. Your story world will be populated by your own characters, settings, motifs, ideas, and themes that are most relevant to you and what you’re trying to say. But by following a road that has been cleared by a legacy of writers before you, you know that the groundwork is already in place to smoothly, clearly, and powerfully tell your story from start to finish. Experimenting with story structure will help make you a better writer, too.

2. Use archetypes for unblocking your story

Sometimes you might have a great idea for a character or a place or a situation, but you’re not sure which direction the story is going to take. By looking at the story archetypes we discussed above, you can narrow down the paths you might go down until you find the one that feels like the right fit.

For example, you may have decided to write about a girl who’s just become the first ever female member of her school’s boys-only sports team. That sounds like it could be a great story—but what next? Try looking at some core story archetypes. Is it a “Voyage and Return?” Maybe the team goes to a major event in another country, an event that’s dominated by men and different cultural values than what she may be used to, and she needs to navigate the obstacles of that landscape and find her place in it.

Is it an “Overcoming the Monster?” Maybe the girl has to prove herself to an adversary who wants her off the team, no matter the cost. Maybe the “monster” is her own insecurities and feelings of not belonging or being unworthy. In your story, you can explore how she overcomes these obstacles to be the best she can be.

Or maybe it’s a story of “Rebirth.” Perhaps the girl has put everything on the line in her battle to be accepted so much that she’s pushed away the people she loves, her academic responsibilities, and everything else that she used to value (this would also reflect Polti’s story archetype, “all sacrificed for a passion.”). Maybe your story explores her journey in rediscovering herself, making up for past mistakes, and learning how to balance the things that matter.

By looking at your ideas through the lens of story archetypes, you can discover new directions and a new understanding of your characters.

3. Combine archetypes to generate ideas

If you don’t have a story idea yet to begin with, these universal archetypes can help kindle some creativity. Try matching different story archetypes to create something new.

For instance, you can start by looking at the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index and choosing a few stories until you feel your ideas starting to simmer. What about “The Clever Fox (And Other Animals)?” That already sounds like a fun story, but it’s not enough on its own. How about “The Clever Fox (And Other Animals)” and “The Man Marries the Princess?” That’s almost starting to sound like a story, isn’t it?

What about… “The Clever Fox (And Other Animals)” and “The Man Marries the Princess” and “Man Outwits the Devil?” What happens if you write a story with all those three elements? You can mix and match story types to get yourself writing things down and coming up with new stories you wouldn’t have discovered otherwise.

4. Use archetypes to communicate a message

Arguably the most important use of story archetypes in writing is to communicate a powerful theme or idea. Because these stories are so universal and so deeply ingrained in our consciousness, they make the perfect vessel for questioning how we look at the world.

To teach your readers something about stigma against the unfamiliar and change, try writing a “Quest” story that mirrors some of the battles our society is facing today. If you want to teach your readers that the whole world is open to us if we show enough resilience, try writing a “Rags to Riches” story that shows us how we’re responsible for our own fate. To show your readers that they’re stronger than they think and can overcome anything they put their mind to, try an “Overcoming the Monster” story in which your hero conquers a seemingly insurmountable foe—from outside or from within.

You can help your readers identify with a specific character in your story to reveal strengths and lessons they can discover within themselves.

Story archetypes connect your story to literary history

Stories are as vast and varied as storytellers themselves, and your story will be as unique as you are. However, by connecting to these universal story archetypes, you’re carving out a place in a proud legacy of writers that’s existed since the birth of language. You can use story archetypes to create new ideas, to breathe new life into old ones, or to show your readers their world in a brand new light.