It’s been said that there are a finite number of stories in the world. It’s also been said that there are more stories in the world that we can ever imagine. Both of these things are true.

New writers often find themselves overwhelmed by the indescribably vast landscape of plot. Maybe you have an idea for a great main character, or a place where you want to tell your story from, or even some glimmers of things you want your characters to be doing in these places. But is that enough for an entire story? Not quite. Your story needs plot—the structural road map that will carry your readers through to the very end. But what is plot, and how do we find the plot of a story? Let’s take a look at some definitions, plot elements, and a few examples to show you how it’s done.

What is plot in a story?

In writing, plot is the sequence of events that guides a narrative such as a novel, short story, play, or film. Every time a character makes a choice or reacts to the consequences of a choice, the plot of the story moves forward. This pattern of cause and effect hurtles the protagonist and everyone around them towards the climax.

There are a few different ways to map out your plot , but in the end most stories follow a pattern of action and reaction. The protagonist takes a step forward, makes a choice, creates something, or puts some new energy into being—this is the action. Then, the reaction: the protagonist’s action triggers an effect that they didn’t expect, or an effect they did expect but that has unintended consequences. In response, the main character takes another action. And the plot pushes back, again and again and again.

How these actions and reactions progress will naturally fall into the rhythmic patterns of storytelling that we call story structure.

Why do I need plot structure?

It’s not uncommon for new writers (or even experienced writers) to have some hesitancy when it comes to formally structuring their work. There’s often the fear that letting your plot fall into a recognizable pattern will make it somehow less original, less distinct, less yours.

It’s understandable to feel this way, but the truth is that all successful stories will naturally follow these patterns because they speak to the rhythms of storytelling that we all have within ourselves. When the plot points of a film or novel deviates too far from these plot structures we will usually feel it in our bones; something in the narrative isn’t working. It’ll begin to feel too rushed and chaotic, or too slow and drawn out, and in either case we’ll begin to lose our sense of immersion. We start to disconnect from it without entirely understanding why.

Plot structure is really just a clear, approachable way of looking at why stories affect us the way they do, why readers and viewers become so invested in the rhythms of these stories, and how we can recreate those rhythms in our own work.

What’s the difference between plot and story?

Plot and story are two literary elements that are inextricably entwined, but are they the same thing? Not quite.

The most important difference is that story establishes a framework of events that supports a larger theme, while plot explores the cause-and-effect relationship of how these events inform one another. To put it another way—story is about the who, where, and when while plot is about the how and why.

For example, the fable “The Tortoise and the Hare” is a powerful story with a strong plot. The story is: “The tortoise and the hare agree to race. Because of the hare’s arrogance, the tortoise wins and learns a valuable lesson about tenacity and commitment.”

The plot is: “The hare challenges the tortoise to a race. The hare runs so fast and is so certain of his victory that he takes a nap before he reaches the finish line. When he wakes, he discovers the slow tortoise has finished the race before him.”

The story gives us a picture of the work as a whole including its character development and theme, while the plot shows us how the story comes to be. You need both in order to create a coherent narrative work that resonances with your readers.

Elements you’ll find in every plot

For any plot to work—whether it’s a short story, novel, screenplay, or any other narrative form—it needs a basic plot foundation. You can think of these essential elements as the “Three Cs” of plot structure: character, causation, and conflict.

Character is the backbone of any good narrative. The most important element of plot structure, a character’s choices are what drive the story forward and encourage readers to empathise with their journey (we’ll talk a bit more about the “Hero’s Journey” story archetype below).

For a reader to care about what your story is trying to say, you need engaging main characters.

Causation is the pattern of factors that influence the events of the plot. This begins with the inciting incident—an external factor that instigates a change in the lives of your characters—and continues with every choice your characters make.

Every turning point in your plot is directly caused by the events that have come before it.

Conflictis what drives your characters to make the choices that they do. One character wants something, and another character wants something, and the plot happens because those desires can’t exist at the same time. Each character takes steps to pursue their goals, and in doing so, unleash an unexpected maelstrom of story.

Sometimes the conflicting goal might come from something like an impersonal organisation, or even a force of nature. You can read more about finding the right conflict for your story here.

The 7 universal stories

Most scholars agree that there are a certain number of plot archetypes which all stories across all mediums follow. What they tend to disagree on is exactly how many plot types there are. Aristotle, John Gardner, Kurt Vonnegut, Christopher Booker, Ronald Tobias, and Georges Polti are all scholars and authors who have tried to compartmentalise the diversity of story. They’ve suggested that all stories are born from a handful of different plot archetypes.

Today, most writers agree on the “seven story format,” which states that there are seven grand, overarching master plots that contain within them all the stories in the world. Many stories will fit snugly into one of these well-worn patterns, or master plots, that have been shaped and perfected over time; others will draw from two or more of these plot archetypes.

Let’s look at the basic plots that form these seven universal stories.

1. The Quest

In a Quest plot type, the protagonist begins with a very clear objective; this may be of his or her own choosing, or it may be something that is thrust upon them. In any case, the main character goes on a journey and faces a string of nearly insurmountable obstacles in order to reach their all-consuming goal: a physical object, a sacred place, an achievement that they can see and feel.

The Lord of the Rings is a classic example of a Quest plot, in which the main character goes through a series of trials in order to reach an object of great power. King Arthur’s story of the Holy Grail and King Solomon’s Mines are other Quest stories.

In contemporary settings, a quest can also be for things like intercepting a hastily sent email, gaining entry into a prestigious institution, or finding a rare copy of a valuable book.

2. Voyage and Return

These types of stories were popular in the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries. They feature a protagonist who goes off to discover a fascinating new place, full of treasures and creatures barely imaginable, before returning safely home with a wealth of new stories to share.

The Hobbit’s well-known alternate title There and Back Again makes it clear that we can expect it to follow this age-old pattern. Alice in Wonderland, The Wizard of Oz, and Where the Wild Things Are are other classic examples of the Voyage and Return.

Although this plot type lends itself very well to fantastical settings, that doesn’t always have to be the case. A protagonist can “voyage and return” to an unfamiliar country, cultural landscape, or class of society.

3. Rags to Riches

This plot type tends to follow this arc not once, but twice: the protagonist begins in a place of disprivilege before coming upon a sudden change in fortune—whether that manifests as money, influence, attention, or love. Then—usually due to their own rash actions—the protagonist loses their newfound glory and has to work to get it back.

The difference in these two story arcs is that the first time the protagonist is usually given their “riches” as a twist of fate, while the second time the protagonist is forced to prove themselves worthy of the riches. Cinderella is a classic Rags to Riches plot, as is the fable of The Ugly Duckling, and Frances Hodgson Burnett’s A Little Princess.

We tend to think of these reversal-of-fortune plots as stories of wealth and class, but they can also come in the form of newfound respect, beauty, or influence.

4. Rebirth

Many of these stories have their roots in Christian mythology, but today Rebirth stories are simply a character arc so dramatic as to affect a complete transformation. Usually these plot types begin with a deeply flawed character who, rather begrudgingly, begins to see the error of their ways and how they can become a better person.

A Christmas Carol is a classic archetypal example of how a thoroughly dislikeable man can, through powerful experiences and deep personal introspection, become someone who makes a positive impact on the world. Beauty and the Beast and The Snow Queen are faerie tales that also follow this plot type.

5. Comedy

Today’s screenwriters know that the ability to make people laugh sells better than just about anything; it’s rare these days to see a film or TV series, no matter the genre, that doesn’t have some lighthearted moments in it.

In classic literature, however, the term “comedy” refers more to a continuous push and pull of dramatic irony—the reader or viewer always knows more than the characters, and we watch with bubbling delight as the cast of players gets themselves into one predictable scrape after another. In many ways, classic comedies show us our own flaws and give us permission to recognize those flaws as part of being human.

That’s not to say that comedies can’t have surprises—often the clever twists and unearthing of hidden secrets are the most satisfying parts of a well-written comedy. But no matter what path they take, the distinguishing characteristic of literary comedies is that they always have happy endings.

Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream is a classic example of comedy. P. G. Wodehouse’s Jeeves and Wooster, and Bridget Jones’s Diary are other stories that follow these patterns.

6. Tragedy

Contrary to comedies, a tragedy plot structure shows us our human failings and how they can be irreparably damaging. They usually follow a character with a major flaw or weakness that leads to their inevitable undoing. Often these are weaknesses that we can find within ourselves, which makes the protagonist’s downfall all the more resonant and compelling.

The Great Gatsby is an example of a modern tragedy, in which the choices the protagonist thinks will lead him to the love of his life are the same choices that send him hurtling towards his ultimate collapse. Oscar Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray and the quintessential tragedy Romeo and Juliet are other stories that show the power of human limitation.

7. Overcoming the Monster

The lifeblood of folk myths, this plot archetype shows an inspiring but very human character facing an opponent made out of nightmares. The “monster” in this case might be a literal creature from the dark; it might be a person behaving monstrously, like a serial killer in a thriller novel; or it might be a monster that lives inside of us, like mental illness or addiction.

Classically, however, the monsters faced were very real otherworldly antagonists. Bram Stoker’s Dracula is a famous example of an Overcoming the Monster story, and the legends of Beowulf and Saint George and the Dragon are ancient stories that have influenced our idea of monsters today.

Drawing on the 7 universal plots to create your own story

These seven plot types have existed since the first cave drawings appeared out of charcoal and firelight—since our ancestors spun stories out of shadows so they could hold onto the light a little longer. Many, many more stories will be written in the generations to come that follow these ancient rhythms.

But don’t feel that you need to limit yourself to just one of these structural outlines. Many successful stories draw from several of these archetypal patterns to create something powerful and new. The Wizard of Oz, for example, follows a character who explores a strange and wondrous land (Voyage and Return), goes in search of a mysterious power in order to help her friends and return home (the Quest), and faces a fearsome witch with her own reasons for taking our heroine down (Overcoming the Monster). This classic tale weaves together several plot archetypes to create something that readers have returned to again and again for generations.

When you begin writing, these seven plot structures will give you an idea of the patterns that storytellers have followed and recognized as great universal truths. Your work will probably draw on several or even all of them as it becomes a part of the neverending tapestry of story.

Plot structures to guide your fiction writing

Now that you know a little more about what the plot of a story is and why it matters in creative writing, let’s look at some classic ways to develop the plot of your story. By using a specific plot structure like ones outlined below, you can create a coherent series of plot points and connected events that will make you story work—every time.

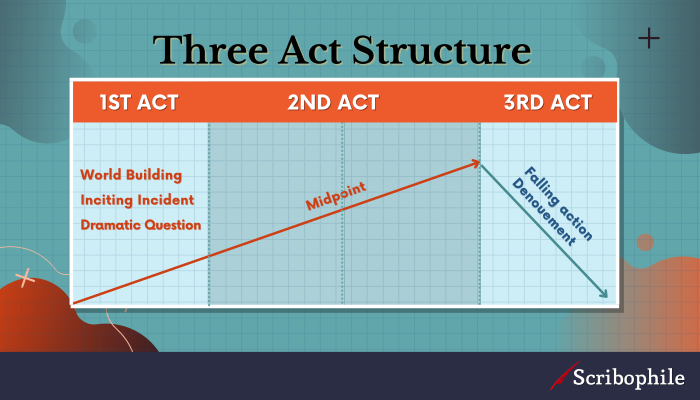

How to plot your story using the three act structure

Human beings have always liked the number three. It’s the number from which our brains begin to recognize pattern, and so over the centuries that number has gained a lot of sacred significance in cultures all over the world. We see it in Christian mythology’s holy trinity, in the triquetra and three sacred trees of the Celts, in three wishes, in three crossroads, in the three witches of Macbeth, and in the three stages of life. “Three” feels complete. This is why the three act structure has remained such a powerful part of our storytelling consciousness for so long.

The first act

Despite being a third of the plot’s structural blueprint, the first act only takes up about a quarter of the plot. However, it packs in quite a lot of important information for such a small section.

The first act does three very important things from which our story can emerge: firstly, it introduces us to the world of our characters. In fantastical settings this includes our worldbuilding—our understanding of the world’s mechanics, politics, systems, beauties, and struggles. Much the same can be said of historical fiction; the first act helps the reader understand the story’s time and place, along with the strengths and limitations that come with that time and place.

Even in contemporary settings we’ll see the world of our protagonist, where they spend their time, who they spend it with, and their relationship to the world around them. This is called exposition, and without it as the foundation of our plot our story can’t exist.

The second is the inciting incident—the moment where our plot is launched into motion. This can be the arrival of a new character or a new piece of information, a disaster that changes the landscape of the protagonist’s world (physically or emotionally), a birth, a death, a choice—something that irreparably ruptures the characters’ world into a before and an after. This is where our story begins.

Lastly, the first act introduces us to our dramatic question. This is directly related to the inciting incident; it creates a question in the reader’s mind that the writer promises to answer by the time the plot reaches its close. Will the hero manage to save the city from imminent destruction? Will the boy reach the girl he loves before it’s too late? Will the heroine manage to escape and find her way back home? These questions are essential to create tension for the reader. Amidst the twists and turns the plot takes as it reaches its conclusion, this dramatic question stays with us continuously until the very end.

The second act

The second act is our major player; it takes up about half of the plot, or the second and third quarters. Once your main character has been thrown into a new set of circumstances by the first act, the second act will raise higher stakes and throw more obstacles in the protagonist’s way. This is where most of your story’s major events will occur.

In a way, the second act almost functions like an entire story arc unto itself. The protagonist spends the first half of the second act reacting to their altered world and being forced to make new choices that will power the direction of the rest of the plot. Around the middle of the second act (the middle of our plot) we reach the midpoint—a false climax that forces our characters into a new kind of action. In The Wizard of Oz, for instance, the midpoint comes when the central characters finally reach their ultimate goal of seeing the Wizard to ask for his help—only to find that the Wizard is not at all what they expected, and they now have a whole new journey ahead of them.

After the midpoint of your plot, into the second half of the second act, your characters will begin to shift from simply reacting as best they can to what they have been given to taking action against it. The choices they make in this third quarter of your plot will bind them to their fates for good, even if they don’t know it yet. Things start to happen much quicker as the characters gain the strength to fight for everything they stand on the precipice of losing.

The third act

Contrary to the first act, which starts off gentle and slow-burns its way towards the second one, the third act erupts with a roar. In this final quarter of the plot, all the writer’s carefully arranged pieces are falling into place. The point of no return for your characters has come and gone like an exit in a rear-view mirror, and now there’s nowhere to go but forward full force towards the plot’s climax.

Where the first and second acts have been a series of choices that your protagonist has made, the third act focuses on the protagonist owning the consequences of these choices and fully committing to seeing them through. This takes us to the climax of the plot—the final piece that will have readers clinging to the edges of their seats, the moment that answers the dramatic question once and for all.

Then, once the dust settles, the characters are left with the new world they have created and the new adventure of trying to find their place in it. Freytag called this the falling action and denouement, which we’ll look at below.

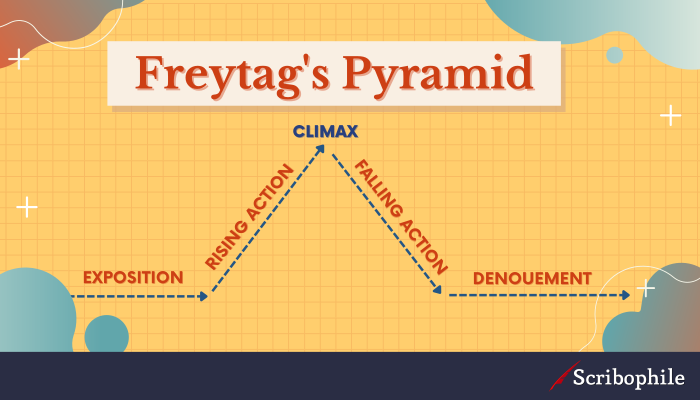

How to Plot Your Story Using Freytag’s Pyramid

Originally laid down by Aristotle and later expanded on by novelist Gustav Freytag, Freytag’s Pyramid is a roadmap of storytelling composed of five pieces: Exposition, Rising Action, Climax, Falling Action, and Denouement. This plot structure is also called the “Dramatic Arc,” and has much in common with the three act structure, approached in a slightly different way.

1. Exposition

The exposition’s role is to immerse your readers in the world of your story. This means establishing your main characters and setting, and giving them a clear idea of what your protagonist’s “normal” world looks like. How they spend their days, the struggles that they face, the things they take for granted. What they have to lose.

This section shouldn’t take up a huge amount of real estate in your plot, but it’s essential in snagging your reader’s interest. Exposition is the foundation on which the rest of your plot, themes, and character arcs are built.

2. Rising Action

The rising action kicks off with the first pivotal moment: the inciting incident. This is the moment where an external force careens into the protagonist’s everyday life (which we introduced in our exposition). In the Harry Potter series, this is the arrival of an innocent-seeming letter written in vibrant green ink. In Pride and Prejudice, the plot kicks off when an eligible new bachelor moves into the neighborhood. The inciting incident is the nudge that gets the plot rolling towards a storm your characters will never see coming.

After the inciting incident the events of the plot begin to gain momentum as the characters react to the new circumstances they’ve been thrust into. Sometimes called “progressive complications,” this portion of the plot is about building up the stakes for your characters within the story’s conflict. Its role is to force the protagonist to make increasingly difficult choices in order to achieve what they want—and what they want might very well change over the course of the plot.

Throughout these progressive complications your character becomes more and more invested in the events of the plot and begins making active choices rather than reactive ones. It’s these choices that lead us to the plot’s climax.

3. Climax

The story’s climax is the emotional crux of the plot, for both the main character and the reader. It’s the thing that will keep the reader huddled up in their blankets with a flashlight long past their bedtime. This is the moment where the protagonist’s fate hangs in the balance as they make one last big, dramatic choice that changes their world—externally or internally—forever. It could be when a driven career woman finally decides to give up everything to be with the man they love, or the moment when a damaged, conflicted hobbit fights with his own desires inside the fires of Mount Doom. The climax is the point when everything you’ve built since the opening of your plot comes together.

If the writer has done their job well in the exposition and the rising action, the reader will be fully engaged in this moment and will experience it with your characters right beside them.

4. Falling action

After the wild, earth-shifting storm of the climax, the landscape of the protagonist’s world will be forever changed. This might be on a larger scale, or it might simply be in their own perspective and values. The falling action shows us how they adapt to this new world and ties off any lingering questions still unanswered. This is also the place where the writer can take a little more time to explore theme and any lessons they want the reader to come away with.

You can think of the falling action like reverse exposition. Like the initial exposition, it shouldn’t take up a lot of space in your plot, but should show your readers what the characters have learned as a result of the story and where they’re headed next.

5. Denouement

The denouement is the resolution, or closing, of the plot. It’s the final scene, moment, or idea the readers see before they finally close the book. In Shakespearean work, this is often when the last character standing faces the audience and shares with them one final pearl of wisdom. This is a small moment, but it should leave the reader feeling that the plot has tied off effectively.

Once you’ve written your denouement and given all of your characters an “ever after” of some sort or another, communicated your theme and tied off any last uncertainties, you get to indulge in one of life’s greatest, most luxurious pleasures:

Writing The End.

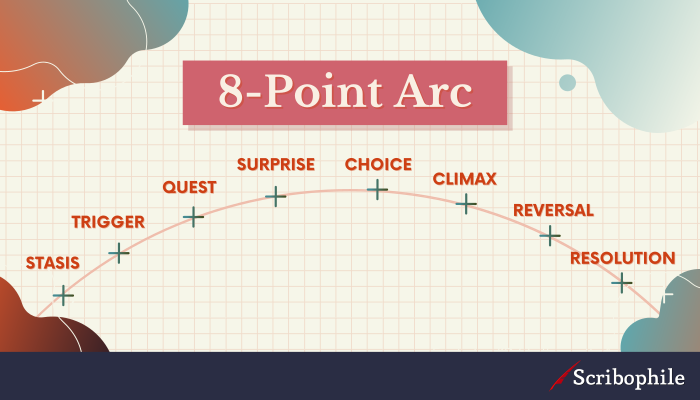

How to plot your story using the 8-point arc

Originally set down by writer Nigel Watts in his book, Writing A Novel and Getting Published, the 8-point arc has similarities to Gustav Freytag’s system while expanding on several plot points. It’s composed of eight steps that take the plot of a story from the opening lines to the resolution.

Stasis

This section establishes the world of your protagonist and what their day-to-day life has looked like up until this moment. For example, the stasis in Cinderella would be a scene of her sweeping ashes from the hearth for her horrible stepfamily.

Trigger

The trigger is what we might also call the inciting incident—the moment where everything changes. It could be a new character, a new discovery, something being given to the central character, or something being taken away. In Cinderella, the trigger would be the moment they receive an invitation to the prince’s ball. This is the first major turning point of your story.

Quest

Because of the trigger, the protagonist now has a concrete objective which leads to the story’s central conflict. This might be to find something, retrieve something, or pursue a pivotal piece of information. The quest in Cinderella is to find a way to attend the ball. She does this by attempting to make her own dress in secret. (Things do not, of course, go according to plan.)

Surprise

The surprise is what we may also know as progressive complications, or rising action. There will probably be several surprising revelations and obstacles along your protagonist’s journey. This is where your tale will show most of its character development. The first major surprise moment in Cinderella is when her fairy godmother arrives and offers her a way to go to the ball incognito.

Choice

All along the path of your narrative, the protagonist will be making choices. However, there will come a moment where they need to make a critical choice between the way things were and the way things could be, projecting the story in a new direction. Cinderella’s critical choice happens when she goes to the ball knowing that she’s risking her family’s wrath.

Climax

The climax happens as a direct result of everything that has come before—stasis, trigger, quest, surprise, and especially the critical choice. This is where the protagonist’s journey becomes all or nothing. In Cinderella, this would be the explosive scene where the clock strikes midnight and Cinderella flees from the ball while her clothes and carriage fall to pieces around her.

Reversal

Because of the effects of the climax and the choices that led to it, the protagonist experiences a reversal of fortunes and of the self. Cinderella has gone back to her wicked family, but she is no longer the same woman she was. The prince arrives to sweep her off her glass-clad feet and carry her into a new life.

Resolution

The resolution is a reflection of the stasis stage; it establishes the new world order and ties off any loose ends in your story. We see Cinderella begin her happy ending with the prince while the wicked family, depending on the telling, might be graciously given a place in the royal court or they might vanish into obscurity. This is the reconstructed stasis where new stories can begin.

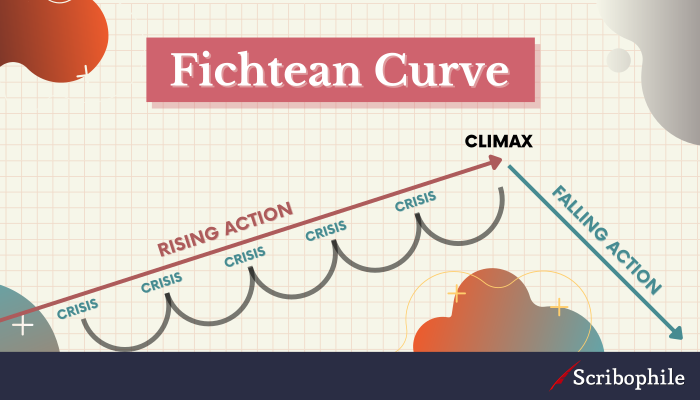

How to plot your story using the Fichtean Curve

The Fichtean Curve story structure is a mainstay of action, thriller, mystery, and horror stories, but it can be applied to any genre. It’s characterised by its intense rising action and episodic complications that build to a big finish. This narrative works best for novels, rather than short stories.

This plot structure is made up of three essential parts: the rising action, the climax, and the falling action. You’ll recognise some of these steps from Freytag’s pyramid, but the Fichtean curve uses them a little differently.

In the Fichtean Curve narrative structure, the rising action forms the bulk of the story. The story begins in media res—i.e., without preamble; it hits the ground running. The inciting incident happens right away and kicks off a series of miniature story arcs, each with its own build up and climax. Every mini climax marks a turning point in the plot. This forms the rising action of the story. These episodic story arcs are great for holding your reader’s attention across the whole story.

“Voyage and Return” and “Quest” story archetypes fit into this narrative structure well, because every stage of your protagonist’s journey can become a story of its own.

Then, each of these miniature story arcs builds on the one before it until they reach the pivotal climactic battle of the story as a whole. While the story until this point has been constructed of smaller stories, each of them has led to this final showdown that characterises the main plot: facing the true monster at the heart of the story’s conflict, meeting the killer face to face, saving the city from complete destruction. This is your story’s climax.

Finally, the story reaches its falling action. This is when your readers get to see how your characters have grown and what they’ve learned from their actions. In a mystery, you’ll explore what happens to the criminals after they’ve been caught; in a horror or fantasy, your readers will see how the central characters move forward after their triumphs and losses.

The falling action won’t take up too much of your story, but it will wrap up any lingering questions your reader might have, tie off all the loose ends in your character’s journey, and hint at what’s to come in your characters’ futures—a happy ending, or a new beginning.

How to plot your story using the Hero’s Journey

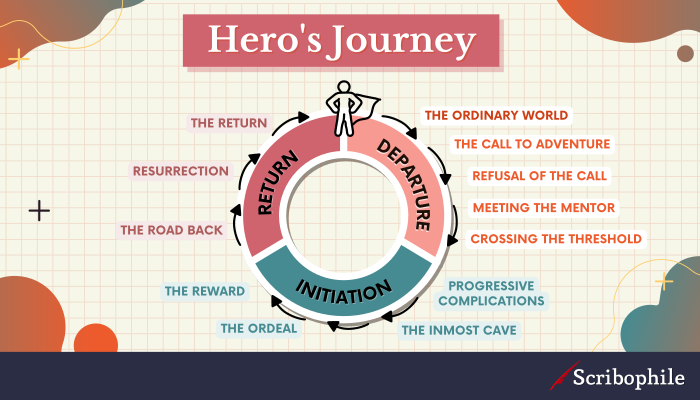

The Hero’s Journey, also known as the monomyth, is one of the oldest and most culturally predominant story archetypes in literature. We see it in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, Star Wars, The Lord of the Rings, and countless other stories of good triumphing over evil. This story follows a central empathetic hero through 12 essential stages as they come into their power and emerge from a cataclysmic conflict forever changed.

Overlaid with the three-act structure, the plot of a story using the Hero’s Journey looks like this:

Act I: Departure

This includes the first 5 steps of the Hero’s Journey: the Ordinary World, the Call to Adventure, Refusal of the Call, Meeting the Mentor, and Crossing the Threshold.

Act II: Initiation

This includes steps 6—9: Progressive Complications (or Tests, Allies, Enemies), the Inmost Cave, the Ordeal, and the Reward.

Act III: Return

This includes steps 10—12: the Road Back, Resurrection, and Return.

Let’s look at each of those stages in a bit more detail.

The Ordinary World

This expository section establishes who your protagonist (the “hero”) is, what their normal world looks like, what they need, and what they have to lose. This tells the reader everything they need to know about your main character before their adventure begins.

The Call to Adventure

In this section, the hero experiences a shift in their understanding of the world (the inciting incident) that drives them onto a new path. How your protagonist reacts will show the reader more of who they are and who they have the potential to become.

Refusal of the Call

Here the hero fights against the impulse to begin this new adventure, fearing loss or change. They may cling to the world they knew and understood, even if it wasn’t perfect, rather than embark into the unknown.

Meeting the Mentor

At this point in the story, the hero meets someone or something that gives them what they need to face the journey ahead of them. This might be knowledge, training, items of power, or even self-confidence.

Crossing the Threshold

The “threshold” is the first point of no return the protagonist faces, where they make a choice to continue and are no longer the same person they once were. This is the first step in their inner transformation.

Progressive Complications (or Tests, Allies, Enemies)

Now that your protagonist has crossed the first boundary between the old world and the new, they’ll begin finding new friends, new enemies, and new challenges. Some of these challenges may be met with resounding success… others, not so much. This is the rising action of your story.

The Inmost Cave

This is the “calm before the storm” where the hero and their allies come together for a moment of recalibration and reflection. They may mourn their losses, celebrate their victories, and plan for the battles to come.

The Ordeal

This is the hero’s first major, climactic battle; it usually appears about halfway through the story. Everything in their journey will have led to this moment, and everything that happens from this point forward will be a result of the action the hero takes during this ordeal.

The Reward

After their major battle, the hero celebrates their victory and the spoils they have won. This might be a physical object, a personal goal, a reconciliation with another character, or a transformative experience.

The Road Back

The protagonist sets off on their journey home, but new complications have arisen from their ordeal and subsequent victory. Now they have to face the new world they have built around themselves.

Resurrection

This is the moment of final crisis for the hero and their loved ones, and the crux of the character’s transformation. The hero faces their ultimate battle and emerges from it changed forever. This scene brings all the themes, character arcs, and lessons together in one epic moment.

Return

The hero finally returns home to the world they left behind, and is forced to carve out a new place within it. They take the spoils they have won, the lessons they have learned, and the experiences they have gained and use them to build a life that incorporates the old with the new.

You can dive into some plot examples and learn about these 12 stages of the Hero’s Journey in more detail here.

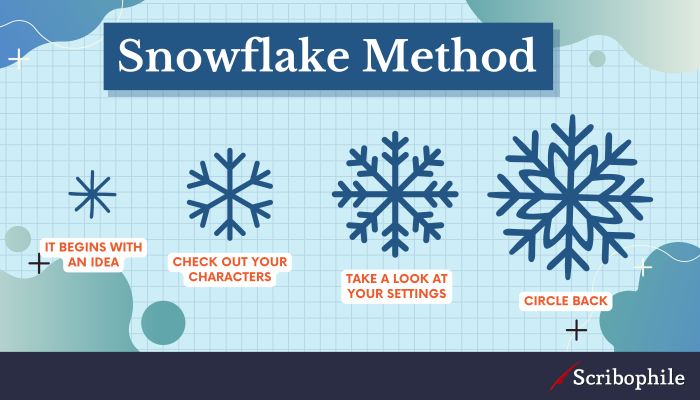

Bonus no-structure plot structure: How to plot your story using the snowflake method

If the idea of pre-designing your plot outline from start to finish seems a little scary, you’ll love Randy Ingermanson’s snowflake method of story plotting—an approachable, organic way to explore the world of your plot before committing it to the page. It was inspired by a mathematical formula and works because unlike more cognitive plot structures, the developmental stage more closely follows the way stories are actually born.

It begins with an idea

Keep it short and snappy and hold onto it because later, once your story is written and polished, it’ll become your sales pitch. Something like… ehhh… a teenager travels back in time to prevent his parents from breaking up. Doesn’t sound too bad, does it?

Check Out Your Characters

You’ve already got three: the kid and two grownups. Write out one or two lines about your protagonist. Maybe he’s creative but also really wants to look cool, so let’s say he plays guitar in a garage band. Give him a name. It can be something silly—you can always go back and change it later. How about… Marty McFly.

Take a look at your settings

You’ve got two so far: the modern day and the time we travel back to. We’ve decided that Marty plays in a band (it’s probably not very good), and maybe he’s looking for a chance to play live. Maybe a talent show or something, so he can impress a girl. Then there’s his parents’ time: think sparkling, pastel-toned nostalgia. You’re writing this all down, right?

Circle back

A teenager travels back in time to prevent his parents from breaking up. Now we know a little more about the teenager, but how does he go back in time? A spaceship? Nah, let’s keep it believable. How about… a car. A really fast car.

Can you see the plot beginning to glimmer in the rough?

Story. Characters. Setting. They begin as simple, unrefined shapes that grow in depth and dimension as you allow more details to come through. The idea behind the snowflake method is that, like a real snowflake, it begins as a tiny crystal and grows layer upon layer.

Write a sentence or two about each of these three components. Then go back and expand each one into a paragraph. By this point you’ll start picking up on other characters waiting in the wings of your plot; give them each a paragraph or two. Get to know them, gently, one layer at a time. You’ll be astonished at how much of your plot is there waiting for you to uncover it. But—and this is important—you need to write it down. It’s through the act of writing that you dig away the raw material to reveal the plot hidden underneath.

Once you’re able to see the roads of your plot more clearly, write a few paragraphs each about your beginning, middle, and end. Then, when you’re ready, when your crystalline plot is humming with possibilities, begin. It’s that easy.

Bringing plot structure into your own story

The three act structure, the dramatic arc, and the snowflake method have all worked well for writers who have used them to create powerful stories. Every writer is an individual, and the one that works best for someone you know or admire might not be the one that feels most natural to you. It’s only through trying, doing, creating, and writing that you’ll learn how to bring your own stories into being.