The five-act structure may sound a little scary at first, but you’ll find that many of your favorite novels and films slip easily into this formula (TV series in particular love this structure because it works well with commercial breaks—remember those?). If you’re someone who loves mapping out your plot before you begin, the five-act structure may be the perfect tool to get you started.

We’ll help you understand the five-act dramatic structure, along with some helpful examples, so you can begin exploring it in your own writing.

What is the five-act structure in writing?

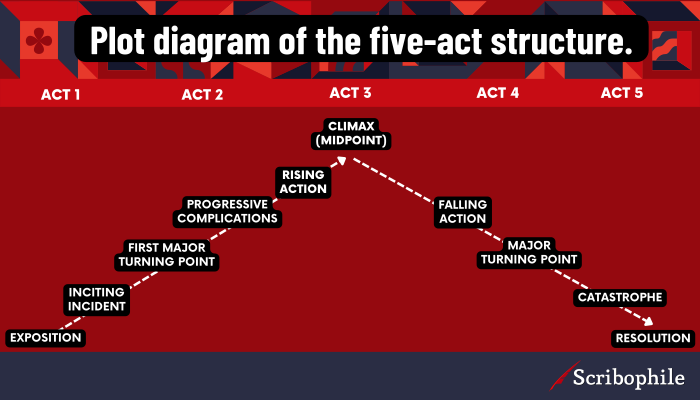

The five-act structure is a plot template in which a story is divided into five sections. Each of these sections plays a pivotal role in the journey the protagonist takes to reach their objective. The distinctive feature of a five-act story is its dramatic midpoint, or hinge, in which the protagonist’s life is split into a “before” and an “after.”

You’ll see the five-act structure being attributed to a range of writers and theorists including Gustav Freytag (who created a plot structure known as Freytag’s Pyramid), Aristotle, Shakespeare, Robert McKee, and John Yorke.

In fact, the five-act structure has been around as long as there has been storytelling. It has found its way into narrative craft again and again because it has been shown to work.

What’s the difference between five-act structure and three-act structure?

The five-act and the three-act structures are types of dramatic forms that create a broad, cohesive story arc for your characters to follow. The most obvious difference between the two, is that one is broken into five acts, while the other is broken into three acts. However, there are other key differences that you can consider when looking at which one is right for you.

In general, the three-act structure tells a more linear story: beginning, middle, end. The inciting incident launches events into action, and everything that follows from that point forward builds towards the final battle of Act III.

In a five-act structure, the plot tends to split into two distinct stories: the world before, and the world after. The climax takes place in the middle of the story, rather than at the end—in a three-act structure this would be the midpoint (we’ll look at these terms a bit more below).

This form works very well for tragedies, because the climax is often the moment the protagonist attains everything they’ve worked for; in the second half of the story, we watch as they sabotage their own victory and lose it all.

But this dramatic structure can be applied to other genres, too. In an adventure, the climax might be the moment the main characters reach a new destination, and then have to learn the rules of it and survive. In Agatha Christie murder mysteries, the first half of the book is usually about getting to know the complex dynamics of the characters; it’s not until the midpoint, or climax, that the murder finally happens. Then the second half of the story focuses on solving the crime.

Not all stories will necessarily fall into one of these structures, but the five-act and three-act story arcs can overlap and many scholars will argue that existing books and films can be examined equally through a five- or three-act lens. However, keeping one in mind as you write can help make your writing process easier and help you move your story in the right direction. You can learn more about writing in the three-act structure here.

The five-act story structure, explained

Now that we know a bit more about why the five-act structure is important in storytelling, let’s break it down further into its individual parts. We’ll examine L. Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz in five acts to illustrate each point.

Act I

The first act is about setting up the protagonist’s world, introducing them to the reader, and highlighting the potential for future conflict to come. Act I is composed of two sections:

Exposition

Exposition introduces us to the story’s “normal” world, the characters within it, and what they want or need.

In a fantasy or science fiction novel, this step is essential in showing the reader how the magical, technological, or political systems work; however, even literary fiction needs this step to help the reader understand who this person is that we’re going to follow throughout the plot and why they should matter to us. It’s exposition, more than anything, that makes your story world real.

In The Wizard of Oz, the exposition shows us Dorothy living with her family in the comfortable but chronically uninspiring Kansas prairies, dreaming of far-off lands.

Inciting incident

The inciting incident is the moment everything changes for your protagonist. This usually comes from an external force such as another character, the whims of nature, or a sudden need that forces the characters out of their comfort zone and into something new.

Without this moment, your protagonist’s life would stay the same as it always was and there would be no story.

In The Wizard of Oz, the inciting incident happens when a tornado lifts Dorothy (and her furry friend) away from everything she’s ever known—and drops her directly into the start of the second act.

Act II

The second act is the rising action, or rising movement, of the narrative. The hero has been thrown into a new world—literally or metaphorically—and now faces new obstacles, meets the story’s secondary characters, makes a whole lot of mistakes, and learns one or two things along the way.

First major turning point

After the inciting incident, the protagonist needs a reason to become invested in the world they’ve been thrust into. This act introduces a pivotal plot point that will give the main character something to fight for and bring them deeper into the story.

In The Wizard of Oz, this happens when Dorothy meets the witch Glinda and learns that her only way home is to travel to the Emerald City. Now Dorothy has a goal in mind.

Progressive complications

Now that the protagonist has something to work towards, they’ll encounter allies to help them on their way as well as obstacles that make their journey more difficult. This is sometimes called the rising movement.

Although your characters will experience setbacks, overall this section will be fairly linear; each scene brings the heroes a little bit closer to their ultimate goal. Gustav Freytag suggested that every character in your story should be introduced no later than the end of the second act.

In The Wizard of Oz, the progressive complications involve introducing the core cast of new friends, facing ferocious beasts (some of the freakier ones didn’t make it into the film; 1930s special effects weren’t quite up to the task), and stumbling into an opioid poppy field.

Act III

In the third act, things ramp up and fast. Finally, everything the protagonist has worked for is within reach. However, things don’t go quite as they expect.

Rising action

With the episodic obstacles behind them and their goal within reach, the main characters have to overcome one final hurdle before they grasp the treasure that they’re after. It is the final moment of no return and the pinnacle of the story’s narrative tension.

In The Wizard of Oz, this is the moment when the four friends finally arrive at the gates of the Emerald City and convince the guardian to let them in.

Climax (or midpoint)

At last, the moment everything has been building toward from the very beginning. The hero has reached the apex of their journey, their holy grail. If you were telling a story in one act, this would be the end of the road. But because this is a story in five acts, the climax becomes the plot’s biggest turning point which sends the protagonist into a whole new adventure.

Some writers refer to the story up until the third act as the “play” and the story that follows the “counterplay.”

In The Wizard of Oz, the climactic moment is when Dorothy and her friends finally meet the Wizard in hopes that he will grant them what they need. Instead, the wizard sends them on a new quest to kill the Wicked Witch of the West before he agrees to help them.

Act IV

In the fourth act, the heroes readjust to their new circumstances and recalibrate their game plans, facing new conflicts to come. This is where we begin to see parallels in the narrative arc.

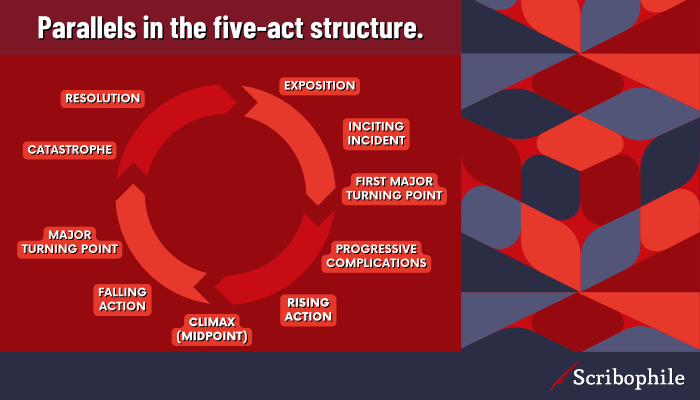

If you imagine the five-act structure as a circle, rather than a pyramid, you’ll notice that the falling action of Act IV lines up with the progressive complications (or rising movement) of Act II, and the major plot point of Act IV lines up with the major plot point of Act II. You can consider the relationship between these parallel moments to give your story a sense of unity and balance.

Falling action

In the falling action, the characters strive to reach new goals and are forced to make difficult choices. In a tragedy, this would be the moment when the protagonist’s life begins to unravel out of control.

This section will raise new questions for the reader, creating tension and suspense as the heroes face increasingly impossible odds. The final outcome will be hinted at, but uncertain. Like the progressive complications, this will often have a linear, episodic quality.

In The Wizard of Oz, this section includes Dorothy getting kidnapped by the witch, the scarecrow and the woodsman being left for dead, and Dorothy finally defeating the witch with a well-timed bucket of water.

Major turning point

Just when the readers think they’ve found their bearings in this new story world, the writer pulls a fast one on them with one last major turn that upends everything we thought we knew. This is the final, biggest complication in the protagonist’s journey.

If you’re examining a story through the three-act structure, this would be the pre-climax, false climax, or “dark night of the soul.”

In The Wizard of Oz, the last major turn happens when Dorothy and her friends return to the Emerald City, victorious, only to learn… that the great wizard is a sham! After everything they’ve been through, he can’t help them after all.

Act V

The fifth act throws one more great, tragic challenge at the protagonist which they may overcome (for a happy ending) or not (for a tragedy). In Act V, we again see a parallel with Act I; the catastrophe mirrors the inciting incident, while the resolution mirrors the exposition. Landing these plot points is essential in making your story feel like a strong, unified whole.

Catastrophe

The catastrophe is the major final scene that brings together all the disparate threads of the story. Usually this will be an irreversible moment of upheaval, such as a battle or the death of a character.

Sometimes, however, the catastrophe can be a positive inversion; in a comedy, for instance, the “catastrophe” might be a big wedding where everyone comes together.

In The Wizard of Oz, the catastrophe happens when Dorothy prepares to leave with the wizard in his hot air balloon, believing it will take her home. However, she’s detained and the wizard leaves without her. You can see the strong mirror image with the inciting incident, here; the hot air balloon that carries the wizard away parallels the tornado that brought Dorothy there—only this time, it’s leaving her behind.

Resolution

The resolution, or denouement, ties up any remaining loose ends and introduces us to the protagonist’s new life—a mirror image of the exposition in Act I. Any subplots will reach their natural completion, lessons will be learned, and themes will be underlined by the end of the story. In the final act, everything is brought to a satisfying conclusion.

In The Wizard of Oz, the resolution shows us how Dorothy had the power to return home all along. The scarecrow, the tin man, and the lion settle into their newly empowered lives, and Dorothy takes the lessons she has learned back to Kansas.

An example of the five-act structure from literature

When used well, the five-act structure has the power to create beautiful, well-balanced stories. Since Shakespearean plays are always a good example of act-based story structure, let’s take a close look at one of literature’s most renowned tragedies: Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet.

Act I

Exposition: We learn about Romeo, Juliet, and their friends, as well as the conflict between the two families.

Inciting incident: Juliet’s family throws a ball with the intention of setting up Juliet and her suitor, Paris. Romeo, his cousin Benvolio, and their BFF Mercutio attend.

Act II

First major turning point: Romeo meets Juliet and falls madly in love. (Rosalind who?)

Progressive complications: Romeo and Juliet discover they’re falling for a member of a rival family and are horrified. In the thrall of headstrong teenage lust, they exchange romantic anecdotes across a balcony. Romeo’s friend Friar Lawrence agrees to marry the couple in secret, thinking it may end the family’s feuding.

Act III

Rising action: Juliet’s hotheaded cousin Tybalt challenges Romeo to a duel. Romeo pleads with him to wait so he can explain that they’ve become kinsmen by marriage.

Climax (midpoint): Tybalt is not having it, and kills Mercutio. Romeo kills Tybalt and is exiled from his homeland in punishment, closing the story’s first half.

Note how by the climax, the hero has obtained the desire born at the beginning of the play: being married to the woman he loves. But just as quickly, it’s all taken away to begin the counterplay half of the story.

Act IV

Falling action: Juliet learns that her husband has killed her cousin and experiences an existential crisis of conscience. Romeo spends the night with her before leaving for his banishment. Juliet’s family arranges for her to marry Paris.

Major turning point: Friar Lawrence comes up with a brilliant and totally foolproof plan: Juliet will fake her own death in order to be reunited with the man she loves. Nothing could go wrong.

Act V

Catastrophe: Romeo, who was supposed to be in on The Plan, only hears that Juliet is dead. He rushes to her side and poisons himself rather than live without her. Juliet, who was never really dead, wakes to find Romeo by her side and stabs herself to follow him into the great beyond.

Resolution: The feuding families come across the bodies of their children and decide enough is enough. They agree to end the fighting for good, and all loose ends are resolved. Despite the tragic circumstance, the story ends on a hopeful note.

How to apply the five-act structure to your own story

The five-act structure is a valuable tool for crafting a story with powerful lessons and giving a satisfying sense of completion to the reader. It’s particularly effective in stories where you want to explore one great, monumental change in your protagonist—for instance, avarice to generosity or prejudice to acceptance. But you can try out the five-act structure in a range of different genres and mediums.

To get a sense of what your five acts will look like, try pinpointing where you want your main character to begin and where you want them to end up. For instance, an Instagram star with a picture-perfect life who grows to appreciate the joy of messy imperfection. Then ask yourself what epic crisis of upheaval (the climax) will turn their journey in this direction. In this case, it might be something like your protagonist getting a six-figure marketing deal that makes them miserable (thereby achieving what they originally thought they wanted).

The goal is to build a trajectory towards this moment, and then a second trajectory away from it. Show your character wanting something, give them what they want, and then show how achieving that desire causes them to want something else. This is, in fact, what so often happens in real life—we pursue a goal, and the pursuit of that goal changes us in unexpected ways, and by the time we achieve it we’ve learned to want something different.

Once you have these three basic building blocks—beginning, apex, end—you’ll be able to fill in the blanks of how they reach each one. You may find parallels emerging unconsciously as you explore your character development and the obstacles they overcome along the way.

Try using the five-act structure to craft a cohesive, compelling story

Act-based structure can be the key to a successful story. As one of the most popular dramatic structures of all time, the five-act structure creates a narrative arc that works in tragedy, comedy, and everything in between. You can try experimenting with this story shape next time you want to give your writing new direction or explore resonant, powerful themes.