Often the story element that makes or breaks a successful book isn’t what you might think—a stellar idea or an explosive climax. Instead, the power of a story rests in its rising action: the ascension of events that carry your protagonist through their journey to a new state of being.

If the term is new to you, don’t worry; we’ll take you through everything you need to know about what rising action means, where it fits into story structure, and tools to make your story’s rising action as powerful as it can be.

What is rising action in a story?

Rising action is the longest part of a story, in which tension is ramped up as the hero encounters progressively more difficult conflicts, meets new allies and enemies, and is taught painful lessons as they make their way along their journey. Rising action comes after the inciting incident and is followed by the climax.

Well-crafted rising action is essential to ensuring your story is engaging, compelling, and carries your reader through from beginning to end. This is where the majority of a story’s tension takes place.

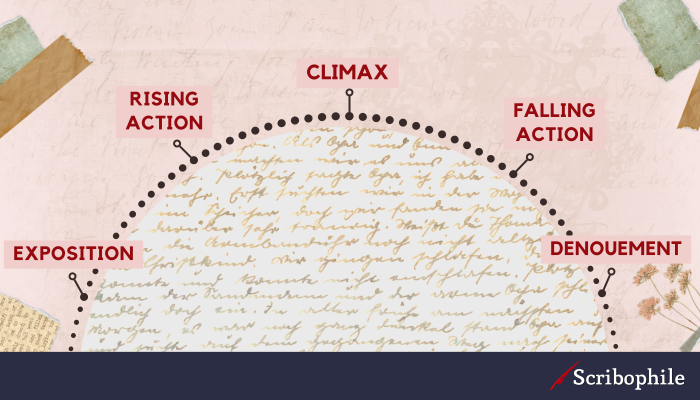

Rising action’s place in plot structure

So where does rising action fit into the broader story arc? Let’s look at the other key plot structure points and how they support, and are supported by, a story’s rising action.

Exposition

In the narrative structure known as Freytag’s Pyramid, exposition is the first plot element of a story. Its role is to introduce the protagonist, their world, their relationships, their wants, their needs, and what they have to lose. Once these elements are established in the reader’s mind, you can introduce the inciting incident—the first key plot point which launches the rising action into play.

Rising Action

Rising action goes here—after exposition, but before the climax.

Climax

Once the rising action begins, everything that takes place in the story will build towards the final, epic climax. The climax occurs at the very end of the rising action and is a direct result of the elements you’ve introduced during this bulk of your story. Without strong rising action, a story can’t have a strong climax.

Falling action

The falling action is the period of resolution immediately following the climax, during which the central characters will deal with the fallout of the events that have taken place. Although it is usually much shorter than the rising action, they will often be reflections of each other. The falling action will lead the story back full circle, showing how the protagonist has learned and grown.

Denouement

The denouement is the last of Freytag’s plot elements, and it refers to the closing pages in which any remaining loose ends are tied up. It will give the story a sense of completion, and hint at where the characters will be going next.

How to develop your story’s rising action

Rising action is all about building tension and moving the plot forward. Here are some things to keep in mind as you develop rising action in your own work.

Introduce a problem to be solved

Conflict is what gets a story moving, and the first step in building your rising action is to give your main characters a problem to solve. This might be the inciting incident, or it might be something that’s directly instigated by the inciting incident.

Some examples might be a miscarried piece of information, a mishap at work, a natural disaster, an alien invasion, a theft, a newcomer with dangerous ideas, and so forth.

This problem might become the main conflict of the story, or it might be something small that leads to a bigger central conflict later.

Make it personal

To create tension and suspense in your story, and to give your main character a reason to fight, find a way to give your problem a personal connection to the protagonist. In other words, the conflict should be something that the protagonist can’t walk away from.

Instead of having your conflict be a jewellery store robbery, what if it’s a robbery of the jewellery shop your main character’s family owns? Then, what if they can’t claim the insurance payout without admitting that they’ve been making some desperate mistakes on their taxes? Alternatively, maybe the suspect of the robbery is the protagonist’s love interest or best friend.

Now, the main character has a personal stake in finding a way to solve this problem before it gets any worse.

Introduce new influences

Once you’ve given your protagonist a reason to move forward, you can begin introducing new influences into the story. Some of these will be positive and some will be negative. You’ll have more space to explore these in a full-length novel than in short stories, but any type of narrative writing will have some new elements added at this point.

These might be things like new characters, new discoveries, more problems (always useful), allies, enemies, or changes of setting. These are the things that will carry your characters from one plot point to the next.

Give your protagonist some victories

Novels where the protagonist suffers unendingly for 800 pages may win a prestigious literary award or two, but… does anyone actually enjoy reading about that much grief? In order to give your readers hope, make sure your main character experiences a win or two along the way.

As they move forward and experience progressive complications, allow them a few moments here and there to catch their breath and celebrate small wins on their way to the final battle.

Give your protagonist some losses

However, don’t make life too easy on them. Along the way, take things away from your characters and show them the consequences of their choices and destructive beliefs. You’ll need both victories and losses along your hero’s journey to keep your reader reading.

Give your protagonist some tough choices

A vital part of an engaging story is forcing your protagonist into moments that test them to their very core. These choices will usually come towards the end of a novel, when the stakes are at their highest point. The protagonist will have to choose between the person they used to be and the person they’ve become, or what they thought they wanted and what they need.

Difficult choices like these are often what leads the main character from the rising action into the climax.

Show how your protagonist has changed

By the time your rising action is reaching its pinnacle and is ready to give way to your novel’s climax, your main character should have undergone some sort of inner transformation. The reader should feel that without this transformation, the climax could not have happened—or, at least, the protagonist couldn’t have emerged from it victorious.

Everything that has happened in your rising action so far will have affected your character in some way so that they can face the confrontation that’s coming next.

Examples of rising action from literature

To see how this plot structure element looks in practice, let’s look at a few examples of rising action in classic stories.

Rising action in “Red Riding Hood”

In this timeless fairy tale, the rising action begins when Little Red doffs her stylish cap and sets out into the woods. The progressive complications include the introduction of an antagonist, the distractions Red faces along the way that lead her from the path, and the iconic battle of wits at her granny’s bedside (spoiler: the wolf wins because Little Red is a wee bit dim).

Depending on the version you’re reading (17th-century Charles Perrault or 19th-century Grimm Brothers), the climax might be when Red gets eaten or when she gets rescued (in the earlier version, there’s no rescue. Red’s death is the end of the story). In the latter, the wolf devouring Red bones and all forms the final plot point in the rising action before the climactic moment of rebirth.

Rising action in The Hobbit

This example of a classic hero’s journey has plenty of rising action: the heroes encounter hungry trolls (enemies), wise elves (allies), goblins, riddling antagonists, and all manner of beasties trying to keep Bilbo & company from their destination.

There are numerous battles between the dwarves and other groups who want a piece of their hard-earned treasure, and even some interpersonal conflicts within the new group of friends.

As the novel climbs to its conclusion, Bilbo makes a character-defining choice; he steals his leader’s most prized possession and goes rogue, using it to try and barter peace. This inversion of Bilbo’s soft, peaceful nature and its recrystallization into strength is a great example of transformative rising action.

Rising action in “The Snow Queen”

This famous novella by Hans Christian Andersen features another kind of journey as a heroine goes in search of her lost love, who has been taken by a cold-hearted (get it?) woman with dubious intentions.

Once the inciting incident has spurred the protagonist into motion, Gerda faces numerous conflicts and makes new friends that help her along her way including a prince and princess, a band of robbers, and a reindeer.

The rising action continues when Gerda finds the boy she’s been looking for, only to learn that he’s on the brink of freezing to death. Just when all seems lost, the rising action moves into the story’s climax as Gerda heals Kai with her tears.

Rising action carries your story to its resolution

As the structural element that takes up the most space in a story, rising action pulls a lot of weight. If your rising action doesn’t deliver, your story won’t feel satisfying for the reader. That’s why it’s essential to pack it full of twists, turns, challenges, victories, and losses through which the hero—and the reader—can fight their way to the finish line.