Choosing the right point of view (or PoV) from which to tell your story is one of the most important choices you can make as a writer. The point of view, or the way in which the story is narrated, determines who tells the story on your behalf—whether that’s a character within the story or someone completely off-page.

The point of view impacts every scene, every sentence, and nearly every word that you write. Unfortunately, making a PoV choice isn’t always easy.

For one, there are lots of different points of view you could potentially use. Sometimes it’s not straightforward how one point of view might affect your story differently from other perspectives. Beyond that, most standard points of view can be further broken down into sub-categories of perspectives, muddying the waters even more.

To help you understand one of these sub-categories, we’re discussing everything you need to know about writing from the objective point of view.

What is the objective point of view?

The objective point of view is a narrative style that views the characters and events within your story much as you might view them on a movie screen. The narrator does not have any insight into the characters’ thoughts or feelings beyond what they show through their actions, words, and expressions.

This can be a very effective choice, because your entire story relies on “showing” rather than “telling.” Objective point of view is a sub-category of the primary narrative points of view, which include first person, second person, third person, and fourth person.

Let’s recap what each of those mean.

First person PoV tells the story from your main character’s perspective (or that of multiple main characters, if you’re using multiple perspectives). You can easily identify a first person narrative via the pronoun “I” to describe the actions and emotions of one character.

Second person PoV pulls the reader into the story and tells it as if the reader is actually living the events on the page. A phrase from a second person PoV story might read as such: “You smell something odd and look out the window to discover that the fire has made its way across your lawn, sending a jolt of fear down your spine.”

Second person PoV is pretty rare, but it is growing in popularity.

Third person PoV tells the story from the perspective of an external narrator looking in at the main characters, their actions, and their emotions. Third person limited focuses on only one character, while a third person multiple or omniscient narrator focuses on many.

This narrating character or voice can be as prominent or unobtrusive as the writer prefers, but third person point of view always describes the action on the page through third person pronouns such as “she,” “he,” “they,” or “it.”

Fourth person PoV tells a story from the viewpoint of a collective group, using “we” to describe the actions and emotions of that group.

Any of these perspectives can be told through an objective point of view.

(You can learn lots more about these perspectives and how to use them in our writing academy!)

How is objective point of view typically used?

Objective point of view is most often paired with third person point of view, because of how removed it is from the story’s characters’ emotions and thoughts. An objective narrator can only observe external events and emotions conveyed through physicality and action.

For example, an objective point of view can see that a character is crying, but the third person objective narrator won’t know precisely why the character is crying unless someone says the reason aloud.

Is the character crying because their brother insulted their baking skills and now they’re embarrassed of their shoddy work in the kitchen?

Or are they crying because that insult sounded eerily similar to something the siblings’ dead mother would say, and now the character is feeling a wave of fresh grief?

We can only make a guess and won’t know unless that character tells someone else what’s going on in a later scene.

Likewise, a character may cry out, clutch their stomach, and grimace, but there’s no way for the third person objective narrator to know what’s causing this reaction. The third person objective narrator can only observe the external signs of pain, but not where it’s coming from or why.

Since the third person objective point of view is completely removed from any character’s perspective, it’s often considered to be the most unbiased and most impartially observant PoV.

Again, think of the objective third person perspective as the same point of view you might get if you were simply watching the lives of a few individuals on a television screen. Better yet, think of that video as the feed from a security camera, not necessarily a cinematic masterpiece. There’s no flashy music, lighting, or tricky editing to make you feel a certain way about any of the events or characters. There are just the characters and the events, presented with no bias and no extraneous information.

First-person objective point of view

While third person objective point of view is most common, there is the occasional use of first person objective point of view. This point of view is best utilized when working with unreliable narrators, because it intentionally removes the reader from the first person narrator’s thoughts and feelings.

First-person objective point of view allows the reader to grow close to the main character, by sticking with them and their actions throughout the entire book or story, with no other focus on any other characters.

However, the narrator is still allowed their secrets because the reader can’t see into their mind or body. This can result in some truly shocking twists, turns, and endings, as the main character’s true intentions, viewpoint, thoughts, background, and other details are revealed, piece by piece, in such a way that heightens your story’s tension.

Should you use the objective point of view in your writing? Pros vs. cons

Given all the above details on objective voice, you can probably guess that using the objective voice is sometimes a perfect choice, but that it’s also a little tricky to pull off effectively.

Here are the pros and cons, so you can decide if this is the best PoV choice for your next story.

Pros of using the objective PoV

When done well, an objective third person narrative can provide your writing, as well as your readers, with a few key benefits.

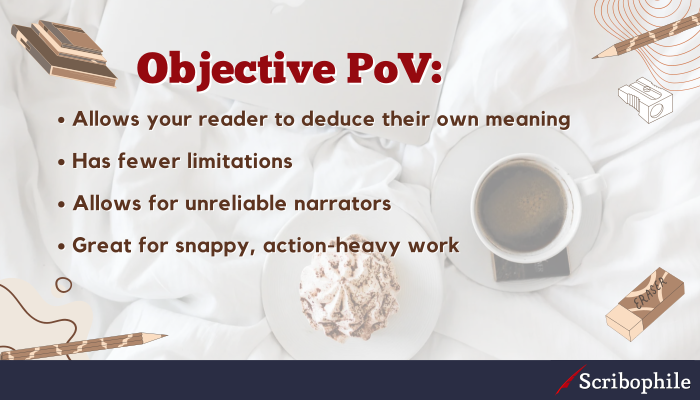

It allows your reader to deduce their own meaning

Firstly, the objective voice is so far removed from bias and your characters that it truly allows your readers to interpret the text on their own.

Since you’re not outright telling them why a certain character did this or that, or what the emotional motive was behind the action, they’ll be able to make those decisions for themselves.

If you want to write a story that will truly make your reader think and reflect, objective voice is the way to go.

It has fewer character limitations

If you find that you’re a writer who really likes to work with a big cast of characters, you may find that objective voice is for you.

Since objective voice doesn’t delve into the thoughts, feelings, and motivations of all the characters, you can broaden the number of characters your story follows.

Of course, you’ll still want to be careful you don’t use so many characters that your story becomes exceedingly difficult to follow, but there’s definitely room to play around.

It allows for unreliable narrators

As mentioned, first person objective viewpoint is particularly a good pick for unreliable narrators, as it keeps your reader close… but not so close that your narrator doesn’t have their secrets.

You can reveal information through external actions and dialogue however best suits your plot, stakes, and the story’s tension.

It’s great for shorter, snappier, action-packed text

Lastly, because there’s that lack of deep diving into a character’s thoughts, feelings, and emotions, objective third person viewpoints allow for snappier, shorter, more action-packed text. You’re able to keep the pace of the entire story or book moving along at a steady clip, which could be a great benefit if you struggle with slow pacing.

Cons of using the objective PoV

Now, here are some of the downsides of using objective PoV in your writing.

It can be difficult to write

The biggest hurdle you’ll want to consider is the simple fact that objective third person perspective can be difficult to write (especially if you have a tendency to head hop between characters anyway, as your narrator describes characters’ emotions and thoughts that they couldn’t have known).

Many writers unconsciously infuse their characters’ thoughts and feelings into the text, whether they’re using a first person narrator, third person omniscient, or any other narrative perspective.

Breaking that habit can be difficult. For that reason, you may want to try your hand at writing an objective point of view short story before you jump straight into a full-length novel.

It doesn’t allow for deep PoV

Secondly, objective voice does not allow for deep dive into your characters’ psyches. In fact, objective voice is pretty much the opposite of deep PoV, which is a point-of-view narration style that is intimately connected to a character’s mind, showing all their thoughts and feelings as if the reader were actually inside that single character.

Does this matter?

Well, it depends on who you ask. There is a trend, particularly in genre literature, for both readers and publishers alike to prefer stories written in deep PoV, as it’s more palatable to today’s readers.

That said, publishing is more open to experimentation than ever before, and people are always open to reading something new.

It requires you to show, not tell

Lastly, as you write this point of view, you have to remember—it’s all up to you. If you want to convey that your character is angry and why, you have to show why and do so in a way that keeps your reader out of that person’s thoughts (and, preferably, in a way that’s not just having your character simply tell another character that they’re mad and why, aloud).

Examples of objective point of view in literature

Ready to see this PoV in action? Here are a few good examples of how the objective perspective works in a well-written story.

“Hills Like White Elephants” by Ernest Hemingway

A good example of objective PoV, “Hills Like White Elephants” manages to convey a tense, emotion-driven conversation between a couple without even once diving into either person’s inner thoughts.

Here’s a passage from the start of this popular short story.

The woman brought two glasses of beer and two felt pads. She put the felt pads and the beer glasses on the table and looked at the man and the girl. The girl was looking off at the line of hills. They were white in the sun and the country was brown and dry.

“They look like white elephants,” she said.

“I’ve never seen one,” the man drank his beer.

“No, you wouldn’t have.”

“I might have,” the man said. “Just because you say I wouldn’t have doesn’t prove anything.”

The girl looked at the bead curtain. “They’ve painted something on it,” she said. “What does it say?”

“Anis del Toro. It’s a drink.”

Throughout this story, the dialogue pulls all the weight. Each word is carefully chosen to convey emotions and tension, while alluding to the couple’s past and problems. The result is a story that’s snappy and quick, without sacrificing impact.

“The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson

Another short story, “The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson is a favorite with fans of the author, full of emotion and tension, but without being based solely on a deep PoV character or a single character’s narration.

Here are a few lines from this classic example, from the opening scene.

Bobby Martin had already stuffed his pockets full of stones, and the other boys soon followed his example, selecting the smoothest and roundest stones; Bobby and Harry Jones and Dickie Delacroix—the villagers pronounced this name “Dellacroy”—eventually made a great pile of stones in one corner of the square and guarded it against the raids of the other boys. The girls stood aside, talking among themselves, looking over their shoulders at the boys, and the very small children rolled in the dust or clung to the hands of their older brothers or sisters.

Soon the men began to gather, surveying their own children, speaking of planting and rain, tractors and taxes. They stood together, away from the pile of stones in the corner, and their jokes were quiet and they smiled rather than laughed.

In this example, the reader can tell something isn’t quite right. What are the stones for? Why are the men smiling rather than laughing? Thanks to the objective point of view, we don’t know and, throughout the story, the feeling that something is very wrong intensifies, heightening the story’s tension right up until the very end.

Objective point of view requires some practice—but can be highly effective

While third person point of view might not be a good fit for every single story, when it works, it just works.

Practice with a few short stories and learn how to use this unique point of view, and it’ll become an invaluable piece of your writing toolkit, to pull out and utilize whenever the moment (or the story) is right.