Fantasy novels are some of our most enduring stories. Many successful writers grew up with them. Through fantasy, we’re introduced to the fascinating idea that there are worlds beyond our own. We can inhabit them for a little while by reading, learn important lessons to carry back with us, and maybe even draw inspiration from them to create our own fantasy worlds.

If you’ve decided you want to write a fantasy novel and aren’t quite sure where to start, this is the page for you. We’ll guide you through everything you need to know about writing in the fantasy genre, including choosing your audience and building a story from the ground up.

Step 1: Choose your fantasy subgenre

It may surprise you to learn that fantasy fiction isn’t just one genre. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings and Patricia Briggs’ Moon Called are both fantasy novels, but they’re very different kinds of stories. Here are the most popular fantasy subgenres on the market.

High fantasy / Sword and sorcery / Epic fantasy

This kind of fantasy goes by a few different names, as you can see. It’s also sometimes called “traditional fantasy.” These stories always take place in a secondary world and incorporate magical elements, fantastical creatures, and high-stakes battles. When people think about the fantasy genre in broad terms, this is usually what comes to mind.

Contemporary fantasy / Low fantasy

“Low fantasy” is a term that’s used to contrast “high fantasy,” and all it means is that these stories take place in our world rather than an imaginary one. The following subgenres on this list will be part of the broader umbrella of low or high fantasy.

Crossover fantasy

Crossover fantasy refers to stories that take place in both a secondary world (“high fantasy”) and a primary or recognizable world (“low fantasy”). For example, the Harry Potter and Narnia series both involve characters who move between one world and another. This kind of novel is especially popular with younger readers, because it hints at a fantasy world just beyond our own.

Urban fantasy

Urban fantasy is a genre which rose to prominence in the 1980s, and refers to stories with fantasy elements which take place in cities. They’ll often have tropes and plot elements which are recognizable from action and thriller novels: organized crime, politics, drug use, and so forth, except viewed through a magical lens.

Magical realism

Magical realism, or magic realism, is a much subtler branch of fantasy which blurs the fantastical and the everyday. Magic is accepted as a part of life, and the conflicts tend to be more internal than external. These novels are heavy with metaphor, with magic being a way to explore grounded themes like coming of age, sexuality, heritage, and so forth.

Dark fantasy

Dark fantasy refers to any kind of fantasy (high or low) with strong horror elements. It may address sensitive or taboo topics, and will usually have more graphic bloodshed than other kinds of fantasy novels.

Cozy fantasy

Cozy fantasy is a subgenre which exploded in popularity during the coronavirus pandemic, during which everyone wanted something to make them feel a little more hopeful. This kind of fantasy is low-stakes and assured of a happy ending. Reading it should feel like a warm hug.

Romantasy

If you’ve been anywhere near TikTok in the past few years, you’ve probably encountered “Romantasy”, a satisfying portmanteau of “Romance” and “Fantasy.” While romantic elements and subplots can be part of all the subgenres we looked at above, romantasy novels have romance as their core focus.

Historical fantasy

Historical fantasy falls under the branch of “alternate history,” in which a period of history is reimagined. The fantasy elements of this genre can be overt, in which everyday people are aware of it in their daily lives, or hidden. Like magical realism, historical fiction fantasy lends itself well to thematic metaphor—for example, the oppression of a magical race as a metaphor for systemic racism.

Sci-fi fantasy

Science fiction and fantasy often get lumped together under the umbrella of speculative fiction, though they’re two very distinct genres. But, they have enough in common that they play well together in a story. These novels have elements of both science and magic, or magical creatures viewed through a scientific lens.

By now, you probably have an idea of what kind of fantasy writer you want to be. Remember, many of these subgenres can be mixed and matched; you could write a historical cozy romantasy and appeal to a range of readers! (But some, like cozy fantasy and dark fantasy or sci-fi fantasy and urban fantasy, don’t mesh as well.)

Step 2: Choose your target age group

Next, you need to decide who you want your fantasy story to be for. Different age groups will be looking for different things, and some subgenres and ideas will work better for one age group than another. It may also affect the voice through which you tell your story.

Middle grade

Middle grade books are meant for children who have just learned to read full-length stories independently (around eight or nine years old) to children of up to about twelve.

These novels are shorter than novels meant for older readers—around 40,000 to 70,000 words (adult novels generally start at 70,000 words). The stories are fairly simple, and although they can have scary parts (for instance, RL Stein built an entire career out of middle grade horror), they’re never too graphic or violent. They often incorporate humor, and are generally fun to read.

Young adult

It’s hard to believe, given its popularity, but young adult fiction is a relatively new distinction. Previously, you would just read children’s books until you were old enough to read adult books. Now, YA is one of the biggest publishing markets.

These fantasy novels are more mature than middle grade (MG) books and often deal with core themes of coming of age in some way. There might be experiences with first love or a first taste of independence, which will resonate with readers on the cusp of their own “firsts.” An average YA fantasy novel is usually between 70,000 and 90,000 words.

Adult

Adult fiction gives you complete freedom to do (almost) anything you want. Apart from the obvious misogyny, prejudice, and hate speech, there are no limits to what you can include in an adult novel.

The cost of this is that adult fantasy readers are more discerning in their fiction, and you’ll have to work harder to create nuanced, human character and complex plots. Adult fantasy novels are generally between about 80,000 and 120,000 words.

All of these age ranges lend themselves well to fantasy writing. However, the way you deliver your story, and the sort of themes you explore, will vary depending on who you’re writing for.

Step 3: Read voraciously

Now that you know exactly which kind of fantasy writing you want to pursue—the subgenre and the target age range—it’s time to start familiarizing yourself with what other writers have done with it. If you’re reading this article, there’s a good chance you’re a fantasy reader already! But where you were previously reading for the pleasure of a good story, you’ll now be learning to read as a writer.

It’s sort of like how professional athletes will watch videos of other athletes and try to pick apart their technique. When you read something you really enjoy, try to break down exactly what that writer’s doing that makes it so effective. If you read a scene that has you feeling unsatisfied—or worse, bored —ask yourself what’s causing that feeling.

Look for the stunningly beautiful sentences, and the scenes that have you on the edge of your seat. Reading in your chosen genre will also give you a sense of what readers are looking for in this kind of book.

Storytelling is a language like any other. The best way to learn is through immersion.

Step 4: Start world building

While you’re doing that, you can get started on writing your own fantasy novel! The first stage is to explore the parameters of this fictional world.

A prominent fantasy author once said, “The joy of world building in fiction is honestly the joy of getting to play God.” As the author, you have full control over everything that happens in this fantasy setting. You can even create a character who looks like your psychologically abusive ex-boss and smite them, if you want to. No judgement.

Here are a few world building questions to ask yourself:

-

Is my story set in our own world, or a world beyond the fields we know?

-

Who lives in this world? Is it populated with humans, creatures from folklore and myth, or entirely new fantasy characters of my own design?

-

Consider the geography and ecology of this place. Is your story set in a big city, a small town, a forest, a desert, or under the sea? What unique challenges does this setting present to its people?

-

Is there magic in this world? If so, does everyone know about it, or is it a secret?

-

Who can use magic? Is it something you need to be born with, or can it be learned?

-

What are the rules of this world? Is there a governing body in place that decides who can use magic and who can’t? What are the punishments for people who break the rules?

-

What major threat is this world facing?

Even if you’re setting your story in the world we see every day (this is called a “primary world”), you still need to determine how the supernatural elements and magic system in place can exist here. It’s these details which will create an immersive world for your reader.

We have tons more tips in our dedicated lesson on world building here!

Step 5: Get to know your characters

You have a place to put your story. Great. Now you need to know who your story is about.

Any story is only as compelling as its main characters. To really hook your reader, you need to develop characters that are relatable and believable. After all, they (and you) are going to be spending a lot of time with them. Here are the starring players of your fantasy novel.

Protagonist

The protagonist is the main character of a story. It comes from a word that means “starring player.” They’re the one who the reader is going to follow across your novel from beginning to end.

Your protagonist is probably the hero of your story, but they may not realize they’re a hero right away (Bilbo Baggins is a classic example of this everyman hero archetype). They should have relatable strengths, weaknesses, fears, and needs, as well as a compelling objective. The objective is the thing they want, and what they spend most of the novel working towards: to go home, to impress their family, to find a cure for a deadly disease, to defeat a dark overlord, to find true love, etc, etc. We’ll look at this more in plot, below.

Finally, a protagonist should have a dynamic character arc. A character arc happens when a character undergoes some sort of change between the start and the end of the story: from cowardly to brave, from selfish to compassionate, from zero to hero—or, if your novel is a tragedy, the opposite direction. A well written arc does two things: it creates character development and momentum, which makes your story feel more engaging; and, it supports inspiring themes that show your readers they have the potential for positive change, too (or negative change if your story is a tragic cautionary tale).

Remember: your main character is going to be the one carrying this entire story and making sure your reader stays interested. So, it’s worth spending some time getting to know who they are, where they came from, what they consciously want, what they need deep, deep down, and why they make the choices that they do. We have some more tips on creating a strong protagonist here!

Antagonist

The antagonist is someone whose goals are in conflict with the protagonist’s goals. This puts them at odds with one another.

Your antagonist might be an evil queen bent on enslaving all the men in the land, or an evil dictator determined to commit genocide of all magical creatures. But, an antagonist can also be more subtle: a family member whose idea of “what’s best” is different from the main character’s, or a friend turned love rival, or a work colleague after the same promotion.

Antagonists aren’t always bad people (though they are sometimes). They’re people who want something, and the protagonist wants something, and they can’t both get what they want. This is where you get conflict, and story.

You can also have more than one antagonist in a story. There’s the primary antagonist (the evil megalomaniac in pursuit of world domination), and several secondary antagonists: bullies, abusive authority figures, well meaning but misguided loved ones, gatekeepers that stand between the protagonist and the next stage of their hero’s journey. The more antagonists you have, the more obstacles your main character has to contend with before they achieve their goal.

An important thing to remember when crafting antagonists for your fantasy stories is that these villains always think they’re doing the right thing. They may be driven by morals and beliefs that are different from our own, but they do believe in something. This gives them complexity and humanity (even if they’re not human in the most rigid sense of the word). You can learn some more tricks for writing compelling antagonists here.

Secondary characters

Secondary characters are the supporting cast that your main characters interact with over the course of the story. This can include things like best friends, sidekicks, love interests, family members, authority figures, rivals, and so forth.

Not every single character in your fantasy book will be a secondary character. There are also tertiary characters, or minor characters, which are the one-shot figures who fill out the story world. Secondary characters should be just as well-rounded and complex as the main character, with their own development and character arcs. Remember—if you were to ask them, they’d say that they’re the real hero of the story!

You can use secondary characters for comic relief, to create new challenges for the protagonist, or to reveal another side of them to the reader. Sometimes, the secondary characters become even more compelling and memorable than the main character.

Step 6: Find your inciting incident

All stories, whether fantasy or literary or somewhere in between, begin with the inciting incident. This is the event that derails your protagonist’s life and sets the story in motion.

Prior to the beginning of your story, the main character was headed in a certain direction. They had a plan —whether that plan was to save up enough money to leave home, to live quietly in their snug little cottage until the end of their days, to marry the most beautiful girl in the village, to complete their apprenticeship, etc. when suddenly…

Stories are born out of “when suddenly”s. Something happens that kicks the protagonist’s plan off course, forcing them to adapt to unexpected new circumstances.

Step 7: Begin building your plot

The best fantasy writers know that a great story doesn’t come out of nowhere. It takes planning and preparation. You’ve already made some headway by exploring your setting and characters; now, it’s time to begin developing the plot using an established story structure as a foundation.

Some writers like to meticulously plan out every single moment of their plot when they’re writing a fantasy book. Others like to work out a general shape of how the plot will progress, leaving room for their imagination to surprise them. It may take some time to discover which method and level of intensive planning work best for you.

Start by looking at some of the most popular story structures: the three-act structure, the five-act structure, Freytag’s pyramid, the eight-point arc, or the Hero’s Journey. The Hero’s Journey in particular lends itself very well to fantasy novels; The Hobbit, the Harry Potter series, and the Star Wars series all use this template.

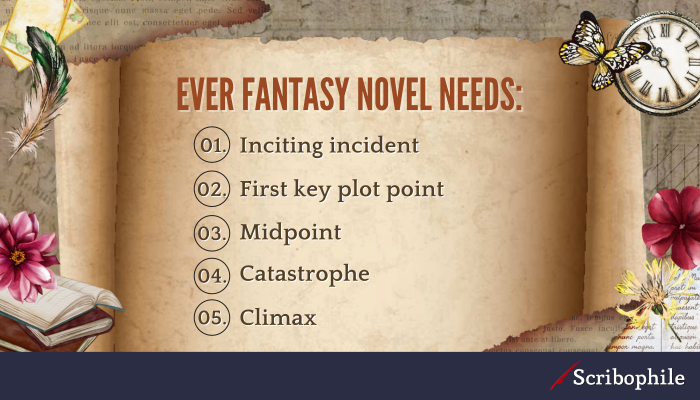

You already have one of your most important plot points: the inciting incident. From there you can build four more important points: the first key plot point (confusingly named, since it’s actually the second key plot point after the inciting incident), the midpoint, the catastrophe, and the climax.

The first key plot point

The first key plot point builds on the inciting incident. It’s a turning point that pulls the protagonist even deeper into the story. For example, The Hobbit’s inciting incident is the arrival of the dwarves party at his door. The first key plot point is when Bilbo wakes up alone, and decides to run after him. The inciting incident is the introduction of a new world, while the first key plot point is the “point of no return” when the main character’s life becomes forever changed.

The midpoint

The midpoint happens about halfway through the novel, and it marks another shift in the protagonist’s journey. Something happens that pushes them from a reactionary stage to an actionary stage. In The Hobbit, the midpoint happens when Bilbo is separated from his party and engages in a battle of wits with Gollum. Previously, Bilbo had been boppin’ along behind the dwarves, going where he was told and just trying to keep up. From this point forward, he begins taking a more active role.

The catastrophe

Then, you have the “catastrophe,” sometimes called the pre-climax. This is a moment of darkness as the heroes hurtle towards the novel’s conclusion. In The Hobbit, the catastrophe happens when the dragon Smaug attacks the town.

The climax

Finally, there’s the climax—the big finish. When you’re writing fantasy, this is often a huge battle between good and evil (in The Hobbit, the climax is the Battle of Five Armies). But a climax can be subtler, too. It might be the moment when the heroine realizes she’s loved her best friend all along, or when the desperate businessman finally decides to follow his heart instead of his wallet.

You may decide to write detailed summaries of each of these plot points and how they link together, or you may just write a few notes so you know where you’re going. Which brings us to…

Step 8: Start writing!

Now, you’ve done all the preparation you need to start writing your first chapter. It can be scary at first, but once you get into a comfortable writing rhythm the words will start flowing more naturally.

Set concrete goals for yourself, and use them to build a routine. Normally writers set goals based on word count or time: for example, write to 300 words or write for 30 minutes each day. On good days, you may go far beyond this goal; on bad days, 300 words can seem like a mountain. Both are inherent parts of the process, as all successful fantasy authors can attest. To help you through the tough bits, consider joining online communities (we have plenty of groups on Scribophile for aspiring authors!) or group writing sprints for some moral support.

Writing a complete rough draft can take anywhere from half a year to several years, so make sure this is a story you want to invest a significant amount of energy and time into. Remember: all the careful planning in the world can’t compare with actually getting words down on the page.

Step 9: Build to a satisfying conclusion

No matter how intricate your world building or compelling your plot, the ending is what’s going to make or break the experience for your readers.

A couple of things to avoid: “Deus ex Machina” endings, which means “God and Machine”, and refers to a sudden rescue by an outside force at the last minute. For example, if your heroes are at the top of a volcano awaiting a fiery death and all seems lost, when suddenly it starts to snow heavily and the volcano freezes over. Ignoring the geophysical improbability of such an event… the heroes didn’t work for this lucky break. It was simply handed to them by the fates as an act of divine goodwill, making for an unsatisfying ending.

Also be cautious of “twist” endings that don’t follow the patterns you’ve established throughout the rest of the story. It’s great if an ending is surprising and fresh, but only if it feels like a natural response to the choices the characters have made. If the ending is tacked on for pure shock value, it probably isn’t accomplishing much else. This will leave your readers feeling a bit cheated and annoyed.

So what does a good ending look like? The ending of your story should feel like a culmination of your main character’s choices since the moment they (literally or figuratively) left home. The protagonist should be able to look back over their adventure and understand that it was never going to end any other way. With each step forward, the number of possible outcomes narrowed until there was only one left.

You may write your story with an ending already in mind, or you may piece it together as you go. If you need some ideas on the different ways you can approach the end of a story, you can check out our dedicated lesson on ending a story here!

Step 10: Practice, practice, practice

No one writes the world’s great fantasy novel on their first try. Writing is a skill just like music or drawing; it takes dedication and practice.

Try writing some fantasy short stories to get your creative wheels turning. Go out and write character studies of the imagined lives of the strangers you pass on the street. Work on developing your skills every chance you get.

It’s important not to get discouraged, especially if you want to build a long-term writing career. Some authors write fantasy for years before landing that coveted book deal, and every short story or novel they create makes them a better writer.

Yes, you can write a successful fantasy novel!

There’s no denying it: learning to write fantasy takes dedication and hard work. But it’s also one of the most rewarding endeavors a person can undertake in their lifetime. Not only do you get to create worlds, characters, and epic battles between good and evil, but you also get to reach readers in a powerful and inspiring way. There’s no time like the present to get started on this magical path!